Beer well served by a fine book

Added: Saturday, June 4th 2022

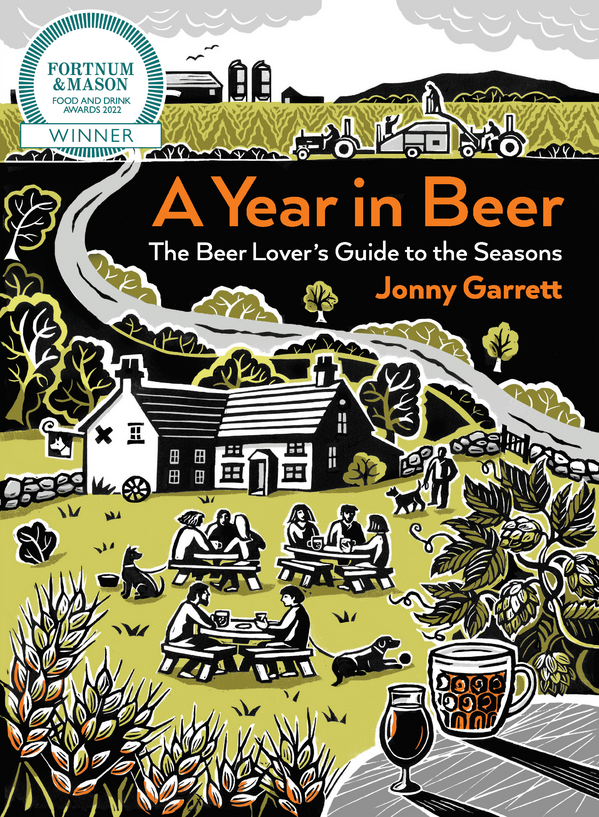

A Year in Beer: Jonny Garrett (CAMRA Books, £15.99)

The evening before I sat down to write this review I found a bottle of Shepherd Neame’s Christmas Ale lurking in a dark corner of my cellar. I drank this delicious beer – bursting with rich honeyed malt and spicy and peppery Kentish hop notes -- with enormous relish...on a warm night in June.

That would make perfect sense to Jonny Garrett who says the way we live now means all the old perceptions of when to drink certain beers can be discarded. We have centrally-heated homes and we don’t need to keep warm with the help of imperial stouts, barley wines and Christmas ales in the winter.

Pop a Pilsner in December if the fancy takes you is Jonny’s advice in this splendid book. I thought back in 1993 when Michael Jackson published his Beer Companion that it was unlikely a better book on the subject would ever be written but A Year in Beer challenges it.

It’s driven by a quiet passion for the subject. It reaches out to a wide audience by assuming not all readers will be well versed in the subject but they can learn a great deal thanks to its informative style and structure.

While Jonny is at pains to stress you should drink the beer you fancy regardless of the season he also argues the case for tracing the roots of different styles by allowing their seasonal origins to take you by the hand.

And so we begin in January with beers that are only brewed in the cooler times of the year. They’re lambic and gueuze, made by wild or spontaneous fermentation, with yeasts in the atmosphere and others locked in oak casks that turn malt sugars into alcohol. It’s a beer that’s dubbed “the champagne of Brussels” but I agree with Jonny that this complex, acidic, tart, vinous and cidery drink is far more interesting and palatable than anything French champagne makers can offer.

Until a few years ago lambic and gueuze were confined to the Brussels region but interest has spread and today many brewers, in the U.S. and Britain in particular, are making what they call sour beers or “sours” – much to the annoyance of the Belgian practitioners, who dislike the terms. Jonny follows the trail and visits some of the British brewers making wild beers, with particular attention paid to Burning Sky where Mark Tranter, formerly head brewer at Dark Star, makes a range of what he sensibly calls farmhouse beers.

Lambic, sour or farmhouse, Jonny says, they make perfect fireside beers for the winter months. It’s also a time of year for hearty dishes to accompany beer. The book doesn’t treat food-matching as an add-on but as an integral element of the enjoyment of beer and each section has recommendations for dishes fit for the table.

February has National Pizza Day, which allows Jonny to not only discuss the various styles of pizza but also to point to the potent links between early bread and beer making in the Old World of Egypt, Persia and Sumeria.

You don’t have to drink cold lager with pizza, though there’s nothing wrong with that if it’s a true lager and not a global glass of fizzy nothing. But Jonny waxes lyrical in his winter section with the pleasures of cask Bitter, a great British institution that’s in urgent need of some tender loving care. He’s critical of the way too many brewers have followed the path set by Molson Coors in rebranding Doom Bar as “amber ale” and praises the likes of Harvey’s and JW Lees in sticking proudly to the name of Bitter. This is a class of beer that needs English hops and one of the finest sections of the book is the beautifully photographed depiction of the harvest of "green gold". Jonny salutes the way hop farmers in this countryt have breathed life back into a dying industry and have developed many new varieties of the plant.

St Patrick’s Day in the spring is the perfect launch pad for a discussion about Porter and Stout. Jonny bravely enters the mine field of the origins of Porter, a style known to have beer writers banging their tankards on tables and even threatening fisticuffs. I think he’s got it right: that in the 18th century in London it was a brown ale that, due to high excess duties, was made with cheap malt, the cheapness masked by heavy hopping. Fresh beer was Running Porter, aged versions were Keeping Porter and a blend of the two became Entire.

But whatever the origins, Porter and its stronger Stout Porter were consumed in vast quantities in London and Ireland with oysters and Jonny recommends this briny combination of beer and food. He also has a recipe for Porter-roasted brisket but several other food offerings concentrate on vegetables rather than meat. I recall a visit to Bamberg in the spring and the pleasure of drinking the local Rauch beers with freshly-picked asparagus.

Mention of Bamberg leads Jonny naturally to German lagers in general, with a wide portfolio of beers that include Bocks, Maibocks, Märzen, Dunkel, Helles and Oktoberfest. And over the border in the Czech Republic, Pilsner is the golden lager that created a style – good, bad and Bowdlerised – that went on to conquer the world.

The book ranges far and wide. Of course, IPA in all its manifestations is covered at length but smaller and more esoteric beers, such as foraged versions made with herbs, flowers, pumpkin and spices, are not overlooked.

The book is a sheer joy. Jonny’s brilliance is to bring beer and its many methods of production to the attention of drinkers in a manner that’s not preachy. It’s like sitting down in the pub with a new friend who tells you, in a conversational manner, things about the liquid in your glass that you didn’t know before. In common with Jackson’s Beer Companion, it will endure and continue to delight people for years to come.

Now, it’s a bit warm today. Where’s that bottle of Harvey’s Imperial Stout?