Dutch beer no longer in thrall to Belgium

Added: Saturday, February 29th 2020

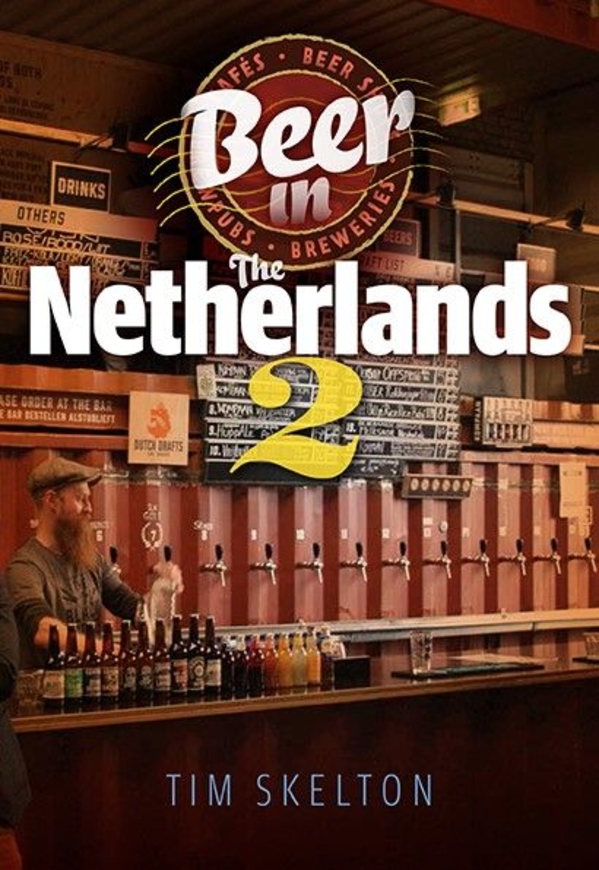

Beer in the Netherlands 2, Tim Skelton (Skelton Ink, £14.99)

It’s one of the idiosyncrasies of the beer world that the Netherlands walks in the shadows of its smaller neighbour, Belgium. The Belgians, of course, enjoy a wealth of fine beers whereas the Dutch for decades have had little to offer but the thin lagers of giant producers.

But as Tim Skelton’s new edition of his book reveals, the Dutch beer scene is changing for the better. When his first edition appeared in 2014 there were 200 brewing companies and 400 good beer pubs. Now there are 600 breweries and the number of specialist beer cafes has grown enormously.

He stresses that readers shouldn’t get too carried away. The beer scene is dominated by just four producers who account for 90 per cent of the beer made and consumed in the Netherlands. What Tim calls “industrial pilsener” represents 85 per cent of all the beer drunk and half of that comes from Heineken. The globals are on the march, taking over smaller breweries: even the wonderful ‘t IJ micro, based next to a windmill in Amsterdam, is now owned by the Belgian Duvel-Moortgat, which has interests in the United States and the Czech Republic, though it’s difficult to think too badly of a group that produces the sublime Duvel.

One problem facing independent Dutch brewers will be familiar to British readers. The government loads duty on beer out of all proportion to the rates paid by wine makers. As a result, it’s difficult for the independents to compete on price with Belgian and German imports. Tim fears this tax burden may drive some of them out of business but, as he says, we should enjoy the ride while it lasts.

And it’s quite a ride. The style of the book will be familiar to users of Tim Webb’s and now Joe Stange’s Good Beer Guide Belgium: a brief history of the Netherlands, travel advice, what to eat and where to stay.

Then we get to the good bits: the A-Z of breweries followed by a listing of beer cafes in the main provinces, from Groningen in the north to Limburg in the south. Beers are given a points system, ranging from one star for “pointless or inadequate” to five for “among the world’s finest beers”. Look out for the latter.

I once asked a woman at a bus stop if I could catch a bus to Amsterdam and when she replied in faultless English I asked why just about everyone in the Netherlands spoke such good English. “Because it’s easier to learn than Dutch!” she replied.

This is emphasised by the very first entry for 013 in Tilburg where the beers include ‘n Steeke Los, Rooie Stien, Kruikje Blond, Op den Ophef and Mooi de Klos. On closer inspection, they are an IPA, a dry hopped IPA, a dry and malty ale, a dubbel and an imperial stout. Learning which letters to drop is part of the drinking experience: for an ex-pat Cockney, it’s good to know there’s a brewery in Friesland called Bjuster: forget the “j”.

Some cafes have more familiar English names but friends should tell the owners of the Dog’s Bollocks cafe in Groningen that the name does them no favours, especially as they serve a dish called Battered Bollocks. You don’t have to be a vegetarian to pass on that.

The update to the entry for Koningshoeven near Tilburg is good news. I’ve visited the Trappist monastery and brewery several times and loved the beers. At one stage, Mammon defeated God and the brewery fell into the embrace of the Bavaria group that specialises in own-label supermarket beers.

As a result, the brewery was expelled from the International Trappist Association and re-admitted only when the monks were able to convince the Vatican they were in charge. While the brewery makes some non-Trappist beers for Bavaria, the range of authentic ales continues. Tim rightly says its four-star oak-aged Quadrupel could improve to world class.

I have an unfortunate track record in the Netherlands. I once visited the Oranjeboom brewery in Breda, which closed soon after. The same fate befell Heineken’s Ridder brewery in Maastricht but both cities are now bursting with great beers, cafes and small breweries. In Maastricht you can sample two of the city’s specialities, Meestreechs Aajt and Maastrichter Maltezer, the latter brewed on the site of the former Ridder plant and is a beer, not a chocolate drop.

Tim Skelton packs the book with fascinating tit-bits. Breda, I learn, has parks where feral chickens roam and the city provided sanctuary for Charles II during the Cromwell inter-regnum.

Most beer lovers will naturally head to Amsterdam, described by Tim as “a hub for loveless sex and the smoking of semi-illicit herbs”. We can put those dubious joys on hold while we go to the profusion of great cafes and micro-pubs in the city. Some of them have approachable names for British visitors, including Beer Temple, Butcher’s Tears and Craft & Draft.

Being a creature of habit, I like to visit bars I know well, including Bekerde Suster, the Reformed Sister, a micro-brewery and bar on the site of an old convent, Elfde Gebod of the 11th Commandment (Thou Shalt Enjoy Life) and the famous Wildeman, handy for Centraal Station. I was, to my surprise, once recognised in the Wildeman where the barman said: Welkom, Mr Protz.” I must ditch the trench coat and trilby.

The guide is a delight, brilliantly researched and written with wit and wisdom by Tim Skelton, a Brit who has lived in the Netherlands since 1989 and has developed a passion for its beer and culture. It’s superbly designed by my old collaborator Dale Tomlinson and it’s as easy on the eye as it is to find your way around.

As Eurostar now goes direct to Amsterdam, I shall make more frequent visits but will watch out for feral chickens and battered bollocks.

•The guide is available from www.beerinprint.co.uk and www.camra.org.uk/books.