Brown to the defence of British boozers

Added: Thursday, August 18th 2016

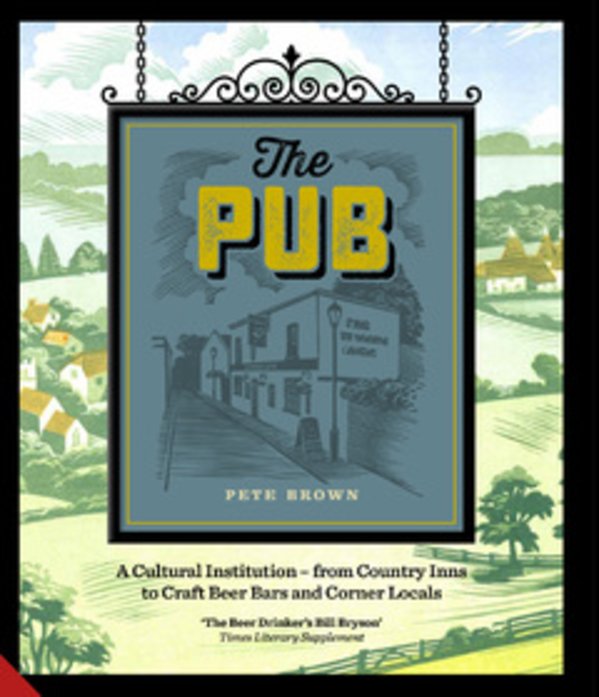

The Pub, Pete Brown (Jacqui Small, £22)

This is just what the battered, beleaguered, benighted British boozer so desperately needs – a handsome book singing its praises. Pete Brown has risen to the occasion with this paean of praise for an institution that is part of the warp and weft of British history and civil society.

I’m pleased the book is called simply The Pub, because there is no such thing as “The British Pub”. Attempts to replicate it abroad are usually risible and downright embarrassing. I recall a man with serious hair dragging me off to see “my London pub” in Mexico City, a place that looked more like the Hot House at Kew Gardens than any self-respecting London hostelry of my acquaintance.

Pete shows that the places where we drink beer and other liquids have grown organically over the centuries. They range from simple ale houses to medieval inns and taverns, the gin palaces of Victorian England, from Brewer’s Tudor to modern incarnations in the 20th century and the spirited rise of the micro-pub today.

It’s the modern micro-pub – often based in such unexpected places as former butcher’s shop, funeral parlours and forgotten railway arches -- that proves the pub is like one of those children dolls that, when you knock it to the floor, comes bouncing back with a big grin on its face.

Many traditional pubs are closing due to a mix of social change, profiteering and downright vandalism. But the institution will mutate and be around for longer – I hope and expect – than the likes of Enterprise Inns and Punch Taverns.

As you would expect with Pete Brown, the prose is sparkling and witty – it’s almost worth the price to read his hilarious but warm-hearted description of the ancient Blue Anchor in Helston in Cornwall, where the regular drinkers are always on the point of departure but never manage to get through the door.

But he’s helped beyond measure by breathtaking photography. There are stunning shots of pubs in town and country, some with lovely sylvan backdrops, others in gritty city streets but all with memorable interiors. There are also fine shots of dogs – one I suspect resides in the Brown house – and the cat in the Seven Stars in London’s Holborn that wears a collar that praises the moggie as “a weapon of mouse destruction”. That’s the kind of oddball humour that makes British pubs so special. When did you last have a good laugh in a French bar or German beer house?

The book starts with a quick canter through the history of pubs with names that reflect often cataclysmic changes in society that led to the Pope’s Head becoming the King’s Head, the Rose & Crown reflecting the victors in the War of the Roses, and all religious connotations ruthlessly removed during the Cromwell period.

We then move into the main sections of the book that are made up of historic pubs, pubs of great architectural interest and community pubs before branching out in the regions of Great Britain and Northern Ireland with Pete’s own choice of drinking places.

Among the 300 pubs listed, some get full page essays, others briefer mentions. We all have our favourites and I am delighted to see some of my best-loved watering holes included. I’m surprised the magnificent Roscoe Head in Liverpool didn’t make the cut and in a few cases disagree with the descriptions.

The Butt & Oyster on the banks of the River Orwell in Suffolk, for example, is described as “a true Wind in the Willows waterside idyll”. No pub could be further removed from the whimsy of that book. It’s a wherryman’s pub, used by legions of tough, weather-beaten sailors taking vital boatloads of malting barley from East Anglia to London breweries. Those gnarled old river men would have given short shrift to Ratty and Moley and helped Toad along the open road with the collective toe of their sturdy boots.

It’s rather unfair to dismiss the Olde Fighting Cocks in St Albans as a tourist haunt – it can’t help being ancient, packed with genuine beams and history. Thanks a vigorous policy masterminded by landlord Christo Tofali, it now has a fine range of beers that makes it popular with locals as well as those bedecked with long-lens cameras.

On the other hands, I’m delighted to find a long essay on another long-time favourite of mine, the Square & Compass at Worth Matravers in Dorset. It has superb views out over the sea beyond St Albans Head, stone benches hewn from the local limestone rock and beer served straight from casks behind a hatch – nothing so sudden as a bar or a handpump. I’m surprised though that Pete, with his keen interest in the juices of the apple and the pear, doesn’t mention that landlord Charlie Newman makes his own cider with fruit picked from Warham Forest.

The book finishes with a flourish: the Bunch of Cherries in Ponytpridd, south Wales where both Pete and I have conducted beer talks and tastings. It’s run by the Otley brothers who also brew in the town. The food and the beer are equally sublime and prove that a pub doesn’t have to be “gastro” or appeal to a small elite but can welcome people of all tastes and social backgrounds.

Like a fine glass of well-conditioned beer, this is a book to sip and savour. It should encourage us to salute and above all use our much-loved drinking haunts.