Restoring name of great Burton brewers

Added: Sunday, January 3rd 2016

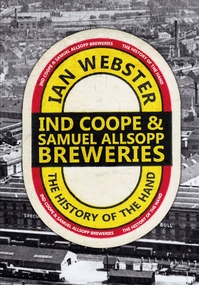

Ind Coope and Allsopp Breweries: the History of the Hand by Ian Webster (Amberley, £12.99)

As Burton-on-Trent has played such a pivotal role in the history of British brewing, especially during the pale ale revolution of the 19th century, it seems remarkable that two of the town’s leading beer makers have been largely forgotten, reduced to footnotes in the town’s folklore.

Across the road from Burton railway station, the sturdy red-brick buildings that were once Allsopp’s brewery are now used as a leisure centre and for some years housed the pub companies Punch Taverns and Spirit. Its neighbour Ind Coope, famously separated by a wall that was demolished when the two breweries merged in the 1930s, was absorbed first by Bass and then by its successor Molson Coors.

Ian Webster has brought the two companies back from oblivion. He tells a fascinating story of two breweries at the cutting-edge of pale ale brewing that transformed beer making not only in Britain but on the world stage. It was Benjamin Wilson’s brewery, later Allsopp’s, where India Pale Ale first became a Burton speciality following its inauguration in London.

The mineral-rich waters of the Trent Valley that gave Burton pale ale its character drew brewers from other parts of England to the small Midlands town. Webster records that the first new arrival was Ind Coope from Romford in Essex, a company that had much in common with Allsopp’s. In 1742 Benjamin Wilson took over the Blue Stoops inn on the High Street while in Romford Edward Ind bought the Star Inn on the bridge over the River Rom in 1799. Both inns belonged to a time when most beer was brewed by innkeepers, before big commercial brewers and tied estates existed.

Wilson and his successors, the related Allsopp family, prospered as a result of the success of Burton Ale, a strong, dark and sweet beer, brewed for export to Europe, Russia and the Baltic States.

Demand led to the acquisition of Sketchley’s brewery on Horninglow Street where increased capacity meant that in one year alone at the end of the 18th century 1,200 barrels of beer were exported to St Petersburg. But as Ian Webster recalls, Allsopp’s and the other Burton brewers, including such major players as Bass and Salt, were plunged into crisis as a result of the wars with Napoleon’s France that led to the blockade of ports in Russia and the Baltic. The story has been told before but it’s worth retelling -- and Webster does it well – of how a director of the East India Company encouraged Samuel Allsopp in 1822 to brew beer for the India trade. Allsopp gave a bottle of the India Ale brewed by Hodgson’s Brewery in London to his brewer and maltster Job Goodhead who created a small batch using – a very English touch -- a teapot.

Ian Webster shows how the industrial revolution enabled Allsopp’s and the other Burton brewers to become the first global beers makers, turning the town into what the Victorians, somewhat pompously, called Beeropolis. Webster traces the breathtaking speed at which, within a few years, Allsopp’s and its local rivals outstripped Hodgson in London and dominated trade with India and other parts of the British Empire. New technology and science enabled the brewers to make beer more efficiently all year round and Burton beers were made available to the domestic market when the railway arrived in the town. To make the best use of the iron way and to keep pace with demand, Allsopp’s built a new, modern brewing plant on Station Street.

The famous red hand logo, which became the signature of the combined Ind Coope & Allsopp breweries long into the 20th century, was registered as a trademark by Allsopp’s in 1876. The red hand was an ancient symbol used by inns to indicate that ale was available and in good condition. Good condition was not a term that could be applied to the company itself. Ian Webster shows that Allsopp’s was quite astonishingly badly run. Following in Guinness’s footsteps, Allsopp’s was floated on the stock exchange in 1866. Far from leading to greater prosperity, sales and profits declined, to such an extent that the directors were booed and jeered at an emergency meeting of shareholders.

The directors blamed the situation on the unfair competition of big London brewers and their development of the tied house system. Yet within a few years, Allsopp’s turned turtle and went on the rampage, buying not only pubs but also hotels. In 1899 it built a new brewery in Burton to produce lager at a time when the demand for German-style beer was minimal in England. This attempt to refashion British drinking habits was an ignominious failure. In total Allsopp’s squandered £1 million.The company had to be bailed out and reorganised and by the early 20th century all members of the ruling family had left the company.

The history of Allsopp’s is well known but we are indebted to Ian Webster for his diligent research into the less well-documented story of Ind Coope. In Romford, Ind Coope had won recognition for the quality of its East India Pale Ale but the directors felt they could achieve greater success in Burton, availing themselves of the waters there. A brewery was bought in the 1850s adjacent to Allsopp’s and Ind Coope Burton grew rapidly, becoming the third biggest brewer after Allsopp’s and Bass.

Ind Coope also became a public company in 1886 but it suffered few of the traumas of its neighbour. It expanded rapidly and the directors reported a doubling of sales as the century ended, accompanied by healthy profits. Success was short-lived, however. Sales and profits plummeted as a recession early in the 20th century hit all brewers. Worse was to come as a result of government policy in World War One, with the strength of beer reduced, accompanied by punitive increases in excise duty to help pay for the war effort.

Ind Coope had to be restructured to stay afloat and there were rumours of a merger with Allsopp’s. But both breweries remained independent, recovered sales in the 1920s but were then plunged into the far worse economic depression of the 1930s that finally forced the companies to knock down the famous intervening wall and become Ind Coope & Allsopp in 1934.

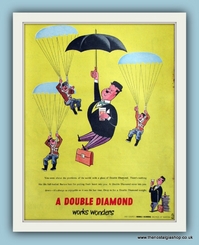

It’s the aftermath of World War Two that forms the most riveting section of Ian Webster’s book. IC&A created two brands – Double Diamond and Skol – that were major successes and yet ham-fisted management and dramatic changes in drinkers’ demands sent them into terminal decline. Double Diamond became one of the biggest-selling beers in bottle and keg in Britain. Its slogan “A Double Diamond Works Wonders” became one of the best-known in the country, aided by the arrival of commercial television in the 1950s. In order to keep pace with demand, a new bottling hall was built and at one stage in the 1950s production ran at an astonishing 20,000 barrels a week.

In the late 1950s, the company launched Skol lager, with the aim of making it an international brand. Enormous amounts of advertising money were thrown at Skol and for a while it was without doubt the biggest-selling lager beer in Britain. But international sales never took off for the simple reason that there were much better lagers brewed elsewhere. Both DD and Skol suffered from over-branding, with DD Export and Skol Extra Strength confusing consumers, and when Skol used a cartoon character called Hagar the Horrible to promote it, the writing was on the wall.

Double Diamond’s fall from grace was compounded in the early 1970s by the arrival of CAMRA with a strident consumer demand for naturally-conditioned ales. IC&A responded with the launch of Draught Burton Ale in 1976. It met with wild acclaim, went into thousands of pubs and to date is the only beer produced by a national brewer to have won CAMRA’s coveted Champion Beer of Britain award.

DBA’s decline and fall has nothing to do with lack of consumer interest but to the endless round of mergers and takeovers that disfigured the last decades of the 20th century. Ind Coope formed Allied Breweries with Ansells and Tetley. Eventually Allied became the brewing division of Lyons, a coffee and cake group with little knowledge of beer. Lyons was happy to hand the beer side of its business to a wines and spirits company, Domecq. Eventually in the late 1990s, Allied Domecq offloaded the breweries to Carlsberg, which formed Carlsberg-Tetley. Carlsberg quickly closed several of the plants and Ind Coope Burton was absorbed into Bass.

Carlsberg’s lack of interest in ale was made clear when it dropped Tetley from its title. Draught Burton Ale moved to Leeds but was soon on the march again, ending at JW Lees in Manchester. Carlsberg finally killed the brand early in 2015.

But Ian Webster can end on a buoyant note. In 2015 he helped brew a new version of DBA at the Burton Bridge Brewery: the beer has been restored to its home town where it has met with great approval.

Ian is a true Burtonian who worked in the Ind Coope laboratory in the 1990s. His book is rich in facts, anecdotes and illustrations and deserves a place on every beer lover’s bookshelf.

*The book can bought direct from the author at [email protected]