CAMRA@50: carry on campaigning

Added: Monday, June 14th 2021

Chiming with the times, I’ve just completed a book on the world beer revival while CAMRA celebrates its 50th anniversary. There’s a lot to celebrate, not least the remarkable choice facing beer drinkers in this country today.

It’s not the same elsewhere. While there are brilliant beers being made around the world, many independent brewers struggle to get their products to market as a result of the terrifying power of global brewers.

Time and again as I researched my book, the figures of 96 per cent and 98 per cent crop up, indicating the market share enjoyed by the globals in many countries. Our nearest neighbour, the Irish Republic, suffers one of the worst situations, with Diageo, owner of Guinness, and Heineken, owner of Beamish and Murphy, controlling 98 per cent of beer sales. There’s now a vigorous small brewers movement in Ireland, offering much-needed choice to drinkers. But in the main they have to sell to restaurants and supermarkets as most pubs, tied to the Big Two, are closed to them.

The picture is even worse in other countries. Great swathes of South America have little but the fizzy apologies produced by AB InBev, where Ambev of Brazil is the dominant partner.

In South Africa, for decades 98 per cent of beer came from just one company, South African Breweries. That became SABMiller as a result of a merger with the American giant, but the group disappeared when it was swallowed by AB InBev in the third biggest corporate takeover in commercial history. As a result, lucky South Africans can now enjoy the delights of American Budweiser, Stella Artois and Corona.

I discovered, just in time to squeeze into my book as a footnote, that despite a pandemic called coronavirus, the beer that shares the name has seen sales rise and it’s now the world’s most profitable beer brand.

Stop the world, I want to get off. Or better still, stay at home.

The situation in Britain is far better as far as consumers are concerned. Of course, the globals hold sway, with Heineken the biggest brewer, followed by AB InBev, Carlsberg and MolsonCoors. But their combined market share is considerably smaller – around 70 per cent – and that gives scope for both regional, family and artisan brewers to thrive.

It’s a far from perfect situation, one that no government of any stripe has tackled. Fortunately, beer drinkers’ interests have been championed for 50 years by a grassroots organisation that has held big brewers at bay, enabled smaller brewers to grow and stopped the country disappearing under a tsunami of fake lager.

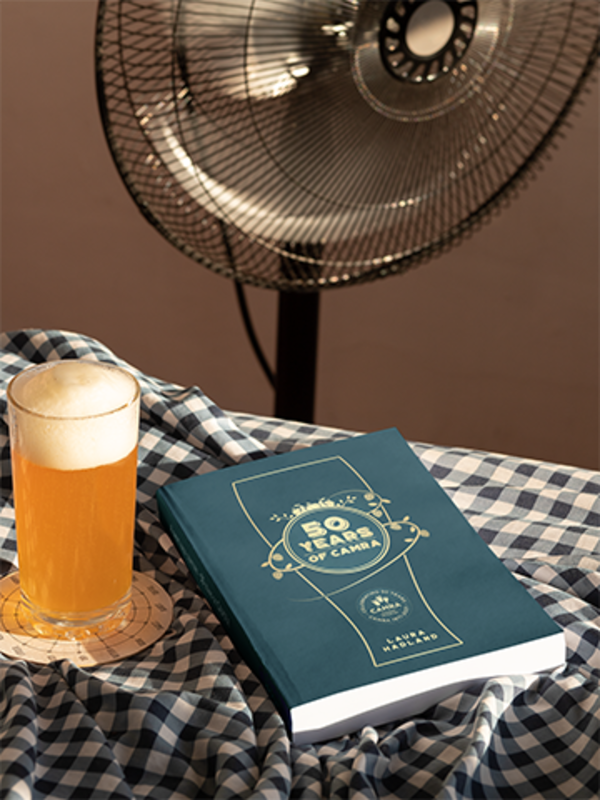

The story is told in 50 Years of CAMRA, by Laura Hadland. Wisely, the campaign stepped outside its own ranks and commissioned someone to write a truly objective, Cromwellian “warts and all”, study. Laura has written a remarkable book, remarkable in the sense that she has achieved the almost impossible: making the internal workings of the campaign seem fascinating.

Did you think you would want to know how the plethora of CAMRA committees, sub-committees, working groups and task groups work? Read on, it’s rivetting stuff. More importantly – and this is the heart-beat of the book – it shows how countless thousands of members devote their spare time to sitting on those committees, and organising and running beer festivals.

In normal times, there are some 12 regional CAMRA beer festivals a month in Britain, alongside the national Great British and winter festivals. The amount of time that goes into setting up these events is mind-boggling and those involved receive nothing in return save for the pleasure of promoting real ale.

The fact that real ale exists is the core of the book. It’s more than just about the internal workings of the campaign. It tells how in the early 1970s a group of dedicated cask ale lovers set out to save this country’s unique contribution to the world of beer.

It was a daunting task. In a mad rush and swirl of mergers and takeovers in the 1960s, six large brewers – dubbed the Big Six – had emerged to not only dominate the beer market but also to close down rivals and change the very nature of beer. Between 1960 and 1971, Whitbread, one of the Big Six, bought and closed 15 breweries and the other giants followed a similar path. In the decade of 1966 to 1976, the number of beers brewed in Britain fell by half, from 3,000 to 1.500.

Most of the beers that disappeared were cask ales. The Big Six were determined to foist on the drinking public a new type of beer called keg – chilled, filtered, pasteurised and heavily carbonated. They were served not from traditional casks but from containers dubbed giant dustbins and the end result was a sweet, gassy and expensive concoction.

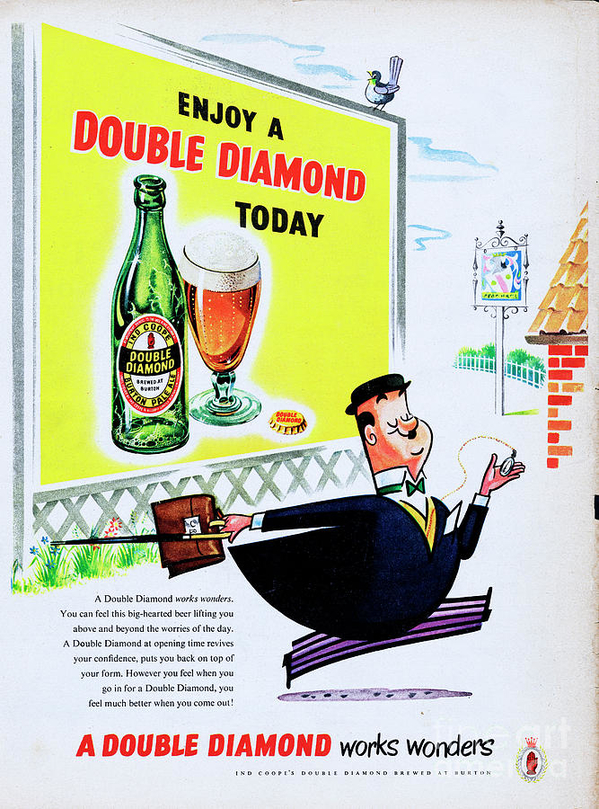

The main keg beers were Double Diamond, Worthington E, Tavern, Tankard, Tartan and the infamous Watneys Red. They were briefly successful not as a result of their quality, which was non-existent, but the huge amounts of money thrown at them. In 1974, more than £1 million was spent on advertising Double Diamond alone, an enormous amount of money at that time.

Their popularity was brief, laughed to scorn not just by CAMRA but by the majority of beer drinkers. The Big Six switched their attention to lager. As more and more Brits started to holiday abroad and got a taste for lager beer, the big brewers developed their interpretations of the style, brilliantly dubbed “ersatzenbrau” by the late, great beer writer Michael Jackson.

One of the major milestones in CAMRA’s history, dealt with at length in Laura’s book, was the 1989 Monopolies and Mergers Commission report into the brewing industry. It was dubbed a CAMRA document in some quarters, even though the campaign was just one of many organisations that submitted evidence. But it bore out what the campaign had been saying since its inception: that the Big Six acted as a cartel, fixing prices, wickedly overcharging for lager and keeping smaller brewers out of the free trade by tying pubs with loans and deep discounts.

The Big Six owned the bulk of the country’s pubs and the MMC recommended that they should be forced by government to turn a large number of them into genuine free houses. The result was the Thatcher government’s Beer Orders that did effectively break up the Big Six but ushered in today’s pub companies – pubcos – with the big players having just as much of a monopolistic mind-set as their predecessors.

But there have been major successes over the years, not least of which was the introduction of Progressive Beer Duty by Chancellor Gordon Brown in the Blair government. CAMRA had worked long and hard with SIBA, the Society of Independent Brewers, to introduce a fairer system of excise duty to aid small brewers who didn’t enjoy the economies of scale of bigger producers. This put them at a serious disadvantage when selling to both the on and off trades. The introduction of PBR, now called Small Brewers Relief, enabled the sector to blossom and grow in a spectacular fashion over the past 20 years.

Today, with more than 2,000 brewers in Britain and abundant choice, it’s tempting say to CAMRA “Thanks, job done”. But Laura’s book should perhaps carry a warning on the cover: “Carry on campaigning”. The power and dominance of the global brewers is unabated and they have shown their intentions by buying or merging with smaller craft brewers. Greene King is owned by Hong Kong property developers. Carlsberg is the majority partner in the new Carlsberg Marston’s Beer Company. Heineken has a substantial minority stake in Beavertown, one of the most innovative of the modern craft producers. Asahi of Japan owns Fuller’s of West London and its subsidiary Dark Star. The Japanese giant also owns Meantime of Greenwich. The trend was set by MolsonCoors that bought Sharp’s in Cornwall and set about turning cask Doom Bar into a mockery of its former self.

In short, defending beer drinkers’ rights needs eternal vigilance. But, as an Irish politician said in a different context, CAMRA isn’t going away. It knows all too well that cask beer has taken a terrible hammering during the pandemic’s pub lockdowns and a major fight back is needed to restore its lustre and popularity.

We’re all of us up for the fight, even those who have grown grizzled in its ranks. Among the many fascinating archive photos in Laura’s book, one that shows British beer writers at the Poperinge Hop Museum in Belgium in 1988 proves that some do not age as well as the product we write about.

•50 Years of CAMRA, Laura Hadland (CAMRA Books, £16.99): www.camra.org.uk. The World Beer Guide (CAMRA Books) will be published in September 2021.