The highs and lows of Draught Guinness

Added: Wednesday, May 13th 2020

“The Two Cask Solution” sounds like a Sherlock Holmes story but there’s been a more modern mystery going round the Twittersphere about the way in which Guinness and other Irish stouts used to be served before the arrival of metal kegs in the 1950s and 60s.

The two casks in Irish bars were racked one above the other. One contained fresh, lively beer, the other mature beer. The glass was filled with fresh beer then topped up with the aged version. After much eddying and swirling in the glass, the beer would settle into the familiar black body and thick creamy head.

The system was explained to me in Cork when I met the retired head brewers at Beamish and Murphy’s, Sean O’Leary and Pat Early. They met for lunch every Sunday, something they had not been allowed to do when they worked, as fraternisation between the staff of the Protestant Beamish and Catholic Murphy’s was frowned on.

They told me that until the 1960s Irish stouts were served by the “high cask and low cask” system. Drinkers demanded a good creamy head on their beer and this was achieved by racking some finished stout into casks, leaving it for 24 hours, and then blending it with unfermented wort [sugary extract] and yeast. The casks were then stored for 10 days while the wort and yeast started a further fermentation.

In pubs, the casks were placed on stillages with the highly-conditioned stouts on the top level and casks with less lively beer below.

“The top casks were known as the gyle casks,” Sean O’Leary recalled. Gyle is a brewers’ term for a finished batch of beer. “The publicans would fill glasses three-quarters full from the high cask and then top them up with flat beer from the low cask.”

The gyle casks had timbers one and a half inches thick to withstand the pressure of the fermenting stout.

The system was labour intensive and time consuming. Pat and Sean told me that as early as the 1940s Guinness started to experiment with filtered and artificially pressurised stout. In the 1950s it introduced pressurised stout served from a horizontal metal container that was nicknamed “the iron lung”. The vessel had separate compartments for filtered stout, carbon dioxide and nitrogen. When the tap was opened, the gasses propelled the beer to the bar where it slowly separated into body and head in the glass.

The iron lung was later replaced by an upright keg. The new Draught Guinness caused such a sensation that Beamish and Murphy were forced to follow suit and abandon the two cask system.

I don’t know if the two-cask system was used in Britain. Research suggests that naturally conditioned Guinness was served from wooden casks until 1963. Draught Guinness in Britain was rare and was mainly confined to specialist Irish bars such as those run by Mooney’s. Most Brits drank bottled Guinness, which was then bottle conditioned.

When I worked in Fleet Street in London, then the centre of the newspaper industry, there was great excitement in the late 1960s when we heard the new Draught Guinness was being served in Mooney’s Tipperary Bar at 65 Fleet Street. I remember queuing to get in one lunchtime and watching the slow serve and the separation of the glass into creamy head and jet-black body.

Time has moved on. Beamish and Murphy’s are now both owned by Heineken. The magnificent Beamish brewery has closed and the beer is brewed at the Murphy’s Ladywell plant. Guinness is owned by Diageo, the global whisky group, and to my taste the beer is a shadow of its old self.

In March, just before lockdown, I stayed in a pub in Liverpool. It had no cask ale and the only draught beer was Guinness. I was astonished at how thin and uninspired the beer was. Where was the famous roasted grain character, with notes of burnt fruit and a solid underpinning of hops? This was thin gruel.

Back in the 1970s, the Leeds-based beer writer Barrie Pepper, who loved Irish Stout and frequently went to Ireland to drink it at source, famously said that if all keg beer had been as good as Draught Guinness then CAMRA would never have got off the ground.

I doubt he would say that today.

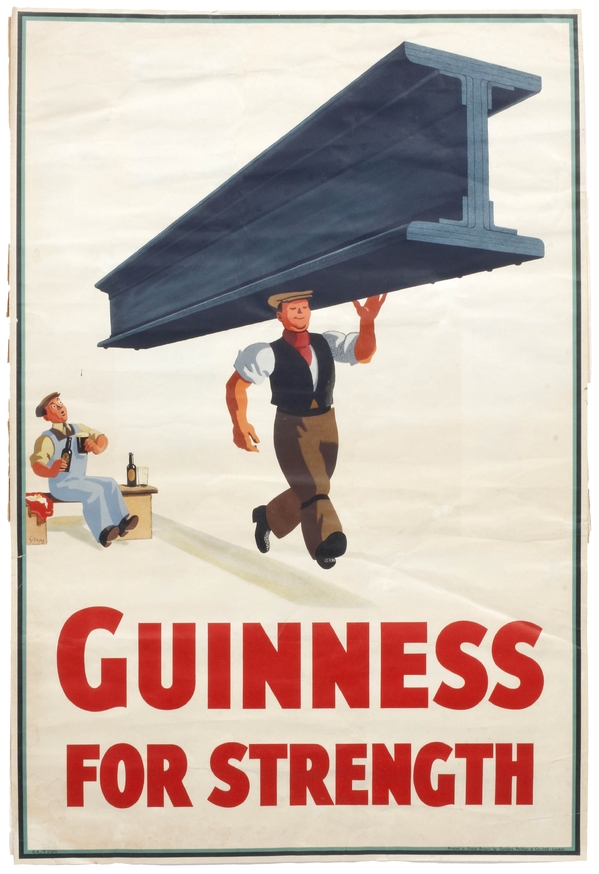

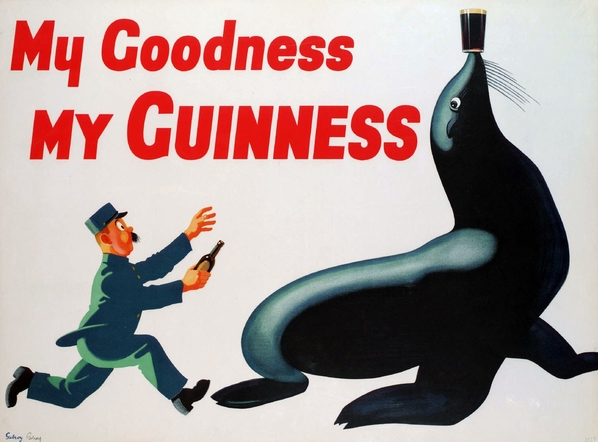

•Guinness’s amazing success in Britain before and after World War Two was boosted in no small measure by the illustrations by John Gilroy for the S H Benson advertising agency (top and below). Benson’s were responsible for the famous slogan “Guinness is Good for You”. The crime writer Dorothy L Sayers worked as a copywriter at Benson’s and she may have been responsible for the slogan

•Serving Guinness at a cold temperature is a modern phenomenon. Both temperature and the method of serving the beer were quite different a century ago, as this passage from James Joyce shows:

“Open two bottles of stout, Jack,” said Mr O’Connor.

“How can I?” said the old man, “when there’s no corkscrew?”

“Wait now, wait now!” said Mr Henby, getting up quickly. “Did you ever see this little trick?”

He took two bottles from the table and, carrying them to the fire, put them on the hob. Then he sat down again by the fire and took another swig from his bottle...In a few minutes an apologetic “Pok!” was heard as the cork flew out of Mr Lyons’ bottle. Mr Lyons jumped off the table, went to the fire, took his bottle and carried it to the table.

Ivy Day in the Committee Room, from Dubliners, 1914.