Beer and pubs in the firing line

Added: Thursday, April 9th 2020

The closure of all the country’s pubs is a drastic step – but it’s not the first time both beer and pubs have been battered by crises and punitive government action.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the politician leading the charge against pubs and drinking was the “Welsh Wizard”, David Lloyd George. He was not only teetotal but he detested the brewers as most of the major ones were staunch supporters of the Tory Party while Lloyd George was the leader of the Liberals.

He cut his teeth in Wales by supporting the powerful temperance movement and the non-conformist churches who won government support for the Welsh Sunday Closing Act in 1881. The result was that while every pub and club was shuttered on the Sabbath, illegal drinking dens called shebeens sprang up in towns and cities where people could carouse long into the night.

The Cardiff brewer Brains complained that publicans running its pubs would watch in frustration from their closed pubs as beer was delivered to neighbouring houses and their regular customers flocked to the illegal premises.

Lloyd George went into overdrive as the new century dawned. The Liberal Party whipped up the temperance movement into a frenzied campaign against the perceived evils of drink and the public house. When the Liberals formed the government in 1905, its Licensing Bill of 1908 sought to reduce without compensation the number of pub licences, to allow people to vote to turn their areas into “dry” ones without pubs, and to ban the employment of women in pubs, which would have put an end to the much-loved British barmaid. Half a million people protested against the Bill in Hyde Park in London, including barmaids dressed in their Sunday best.

The Bill was eventually thrown out by the House of Lords but Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, wasn’t giving up. In 1909 his Budget increased both beer duty and the price of a pub licence. The result was a highly unpopular increase in the price of beer, from 4d a quart [four pints] to 5d. The Budget was rejected by the Lords. The price of beer returned to 4d a quart but the political implications of the defeat were far-reaching, with a Parliament Act of 1911 restricting the power of the Lords to block legislation that had been approved by the Commons.

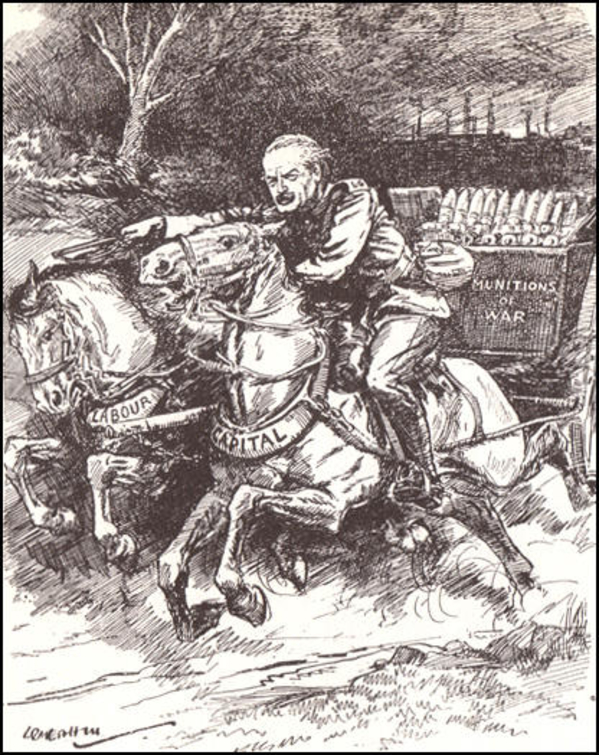

There was no one to block Lloyd George when World War One broke out. He became Minister of Munitions and he had unbridled power to shackle his old enemies, the brewers. In August 1914, the government brought in the Defence of the Realm Act, known as DORA, which gave the Home Secretary powers to control the production and supply of alcohol. This was followed by the Intoxicating Liquor Act that gave magistrates the power to limit pub opening hours on the recommendation of chief constables. Permitted opening hours were cut from 16 or 17 hours a day – the pre-war norm – to 5½ hours during the week and five on Sundays. As a result, consumption fell dramatically.

While the government rejected total prohibition, it did consider nationalising the brewing industry but backed away when civil servants produced figures showing the cost of compensation would be around £225 million. Lloyd George was not satisfied. In an infamous speech in Bangor in 1915, he ranted: “Drink is doing us more damage in the war than all the German submarines put together. We are fighting Germany, Austria and Drink; and as far as I can see the greatest of these three deadly foes is Drink.”

No evidence has ever been produced to support his claim that drunkenness was affecting the war effort but he had the required affect. In June 2015 the government created the Central Control Board that slashed pub opening hours further and banned “treating” – buying a drink for another person, putting paid to the old pub habit of “standing your round”.

The Control Board set up the State Management Scheme that took over pubs in three key areas affecting the war effort: Carlisle and Gretna where a large munitions factory was based; Enfield in North London, which had another munitions factory and was famous for the Lee-Enfield rifle; and Invergordon and Cromarty in Scotland, where a naval dockyard was based. The impact on Carlisle was especially draconian. Five local breweries were nationalised and four of them were closed while all the pubs on either side of the Solway Firth were taken over by the state in an area covering 500 square miles. The Control Board shut around half the pubs in central Carlisle and all off-licences. (Above, the Carlisle Arms, shuttered and barred after the war.)

The pubs that survived were re-modelled as “Improved Pubs” and the model was rolled out to other parts of the country. In Carlisle the services of an architect called Harry Redfern, who was influenced by the Arts & Crafts Movement associated with William Morris, was used to redesign pubs. Advertising was removed from walls, as were cubby holes and snugs. “Perpendicular drinking” was banned in the belief that people got drunk faster standing up. Customers were encouraged to eat as well as drink and the pubs had spacious dining rooms with waitress service. One critic said the pubs looked like third-class waiting rooms at railway stations.

Offering hot meals to people during the privations of war was well intentioned but as beer became more expensive the very people the pubs were supposed to help – poorly paid munitions workers – were driven away and replaced by more affluent middle-class customers.

The reason why beer had become more expensive was simple: the government massively increased duty throughout the war, with Lloyd George in the driving seat as munitions minister and then Prime Minister. One of the first acts of the government in 1914 was to increase beer duty from 7s 9d to 23s per standard barrel of 1055 degrees gravity – approximately 5.5 per cent alcohol in modern terms. There were higher rates for stronger beers. Duty rates were further increased in 1917 and doubled a year later. There was no respite when the war ended as the peace had to be paid for. Duty was raised to £3 10s in 1919 and to £5 in 1920. By 1920, duty raised £120 million for the government compared with £13.6 million in1913-14. In real terms, allowing for war-time inflation, the increase in duty between 1914 and 1920 was a staggering 430 per cent.

The impact on beer was disastrous. With supplies of grain restricted and most going to bakers, brewers were forced to reduce the strength of their beers. In Burton, such legendary beers as Burton Ale disappeared for the duration of the war while IPAs at 3.5 per cent alcohol made a mockery of the original style. Strong stout all but disappeared though the government didn’t dare impose restrictions on the Irish brewers.

The Improved Pubs in Carlisle have long since disappeared while the State Brewery was privatised in 1973. It was run briefly by the Yorkshire brewer Theakston but has since been turned into student accommodation. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the restricted opening hours for pubs were swept away: the grim ghost of David Lloyd George haunted the nation’s watering holes for many decades.