Audit Ale: taking account of history

Added: Tuesday, October 18th 2016

You brew Audit Ale with a sense of reverence and respect for history. It’s an ancient beer style, dating back to the 14th century and is closely associated with the ancient universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

Its method of brewing has close links to the October Ales that are believed to have been the inspiration for the early India Pale Ales of the late 18th and 19th centuries. Both types of beer were brewed with the first grain and hops from the annual harvest and then aged for several months – until January or February in the case of Audit Ales.

Titanic Brewery in Stoke-on-Trent, one of the country’s leading independent breweries founded by Keith Bott – a key figure in SIBA, the Society of Independent Brewers -- is organising a series of beers brewed in collaboration with well-known people involved in beer and brewing. The first beer was made with Andrew Griffiths MP, immediate past chairman of the influential Parliamentary Beer Group, and I was delighted to be second in line.

As my choice of beer would be brewed at the White Horse Brewery near Oxford I immediately told Keith that I would like to make an Audit Ale as a result of its close associations with Oxford colleges. White Horse, which owns the Royal Blenheim pub in Oxford, opened in 2004: its beers include Dark Blue Oxford University Ale. It’s run by Andy Wilson, a former professional Rugby League player with Wakefield Trinity who has also played American football.

He worked at Titanic before opening White Horse and Keith Bott has a 40% stake in the brewery. As it’s considerably smaller than Titanic, producing around 3,000 barrels a year, Keith uses the White Horse kit for both trial and collaboration brews.

The Oxbridge colleges were landlords as well as places of learning, owning large tracts of lands, houses and farms. As a result, they had large incomes from rent. Every year, at the time of the annual audit, a special feast would be held with tenants invited to join their landlords for food and drink. To mark the occasion, the colleges would either brew their own beer if they had breweries or commission commercial brewers to supply them. The last Oxford college brewery, at Queen’s, was closed at the outbreak of World War Two as the authorities feared the town would be bombed as a result of its proximity to the Cowley car plant, which had been turned over to tank production.

For many years, Lacons Brewery in Great Yarmouth supplied Audit Ale to Trinity College in Cambridge while the Black Eagle Brewery in Westerham in Kent delivered supplies to London colleges and to Sir Winston Churchill’s country home at Chartwell, close to the brewery. A local historian says it’s not known whether Sir Winston himself drank Audit Ale but I think we can safely assume the old boy would not have missed the opportunity to drink strong alcohol.

And strong they were. We cannot know precisely the strength of ancient beers before proper measurements were used but they were certainly as powerful as full-bodied wines. One 19th-century American visitor who joined an Audit Feast said the beer was as fine as Chateau d’Yuem while John Bickerdyke, author of Curiosities of Ale & Beer in 1889, compared Audit Ale to Chateau Lafitte.

Both the reborn Lacon’s Brewery and Westerham Brewery are producing Audit Ales again. I didn’t want to copy their recipes and carried out some research to design one for White Horse. It was a remarkably simple beer.

We couldn’t match the strength of historic Audit Ales as the new excise duty rate on strong beers is punitive and the final ABV will be just below 7.4%. With head brewer Nathan Beet (top) in charge and Keith Bott (adding hops) as his second brewer, we began with an original or starting gravity of 1075 degrees. From Crisps Maltings in Suffolk, we used Flagon extra pale malt and dark crystal at the rate of 230 kilos of pale and five kilos of crystal. The hops, in pellet form, were traditional East Kent Goldings and Fuggles.

At 8am we clamber to the top of the brewery to grind the malt, which then flows down to the mash tun where it’s mixed with hot water or “liquor” in brewer’s-speak. The brewing kit at White Horse came from a small Belgian brewery and is typical of the “farmhouse” style of the country, with the mash tun doubling as the boiling copper.

The sweet wort from the mash is filtered in a second vessel, the lauter, before returning to the mash tun for the boil with hops. The local water is soft and Nathan adds gypsum to harden it and accentuate the aromas and flavours of malt and hops.

We are aiming for 6½ barrels of beer. We wait patiently for the liquor in the mash tun to reach 63 degrees C to start the conversion of starch in the grain to brewing sugar. The mash takes 1½ hours, when Nathan is satisfied that a full conversion of the starch has taken place.

The sweet wort is pumped to the lauter vessel where the liquid is removed from the spent grains. Nathan explains that he can’t fit all the grain into the lauter as it’s such a strong beer and he will have to split the mash. The wort then returns to the mash tun for the boil with 750 grams of Fuggles and 650 grams of Goldings, energetically heaved into the tun by Keith. The temperature before the boil is 65 degrees. We are aiming for 30 to 35 units of bitterness: we are not looking for extreme hoppiness or bitterness as contemporary reports indicate the original Audit Ales had a rich malt character. Nathan adds more hops towards the end of the boil and will add further hops – known as dry hopping – when the beer is in cask.

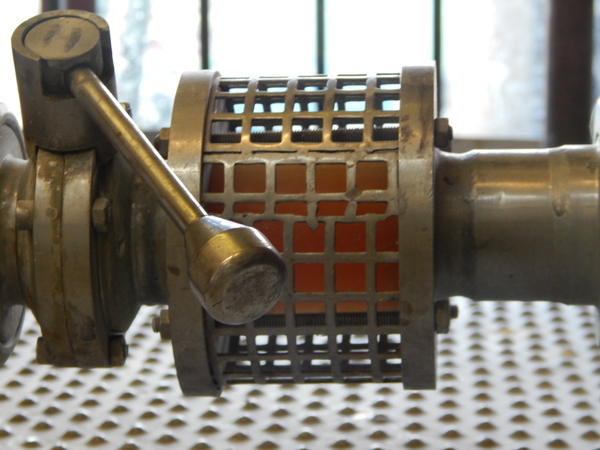

As the wort travels back to the mash tun for the boil it passes through a glass viewing tube (below) and we can admire the bright copper-red colour. A delicious aroma of biscuits and sultana fruit fills the brewhouse: we know we have something special in store.

At the end of the hour-long boil, the hopped wort is cooled in preparation for its transfer to the fermenters, where the wort will be thoroughly pitched or mixed with a Nottingham yeast culture.

Nathan now has the unenviable task of digging the spent grain and hops from the vessels, which will be taken away by a local farmer as cattle and pig feed.

By 3pm our work is done for the day. When fermentation is complete, the beer will go into cask. Keith Bott is looking into the possibility of obtaining a wine or port barrel in order to give the beer a vinous finish.

Then we have to wait. The plan is to offer the finished beer next April – the month when modern accounts are finalised – to university bars in Oxford. Roll on spring.