Flanders Beer Trail 3: husband-and-wife team bring pride back to Hoegaarden

Added: Wednesday, July 10th 2013

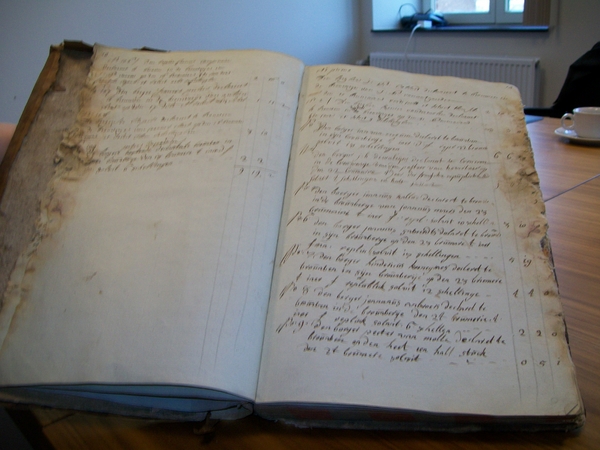

They take beer seriously in Hoegaarden. The rooms in the town hall are named after beer styles and in Grand Cru, overlooking the impressive square and church, I was shown a battered old record book (above) listing all the brewers in the town, which had a brewers’ guild from 1560.

To emphasise the tangled history of the area, some of the entries in the book are in French, others in Dutch. The earliest brewery in the town dates from 1318 and was based in a convent, though monks, not nuns, carried out the brewing duties.

In the 18th century, Hoegaarden, which today has a population of 6,000, had 40 breweries, a remarkable number made possible by local politics. While the town is Dutch-speaking, part of modern Flemish Brabant, in the 1700s it was an enclave of the Prince-Bishop of French-speaking Liège, and he allowed citizens to brew beer without paying taxes. Thanks to this largesse, people became enthusiastic brewers and exported their beers to Antwerp and beyond.

Many of the Hoegaarden brewers were also farmers and they developed a characteristic style of “white beer” made with home-grown barley, wheat and oats. They spiced their beers with such exotic ingredients as coriander seeds and curaçao orange peel, brought to the Low Countries by seagoing Dutch traders.

The French Revolution abruptly put paid to the power of the Prince-Bishop of Liège, and brewers in Hoegaarden, in common with ordinary mortals, had to pay tax. The number of brewers went in to rapid decline as a result. The fall became cataclysmic in the 20th century with the onslaught of Pils lager made by big city brewers. In 1957, the last brewer of Hoegaarden white beer, Tomsin, pulled down the shutters.

Enter Pierre Celis. The legendary brewer of white beer started his working life as a milkman but he’d also done some part-time work at Tomsin’s as a schoolboy. Encouraged by his friends, he started to brew at home and his beer met with sufficient approval for him to move in to a former lemonade factory. Hoegaarden White, served in a distinctive hexagonal glass, became a cult beer, especially among younger drinkers in the university city of Leuven.

Fate took a hand. Pierre’s brewery was devastated by fire in 1985 and he needed funds to rebuild it. Stella Artois, then an independent Pils brewer in Leuven, offered to invest and for a time the relationship was mutually beneficial. But when Stella merged with Belgium’s other big Pils brewer, Jupiler, to form InBev, the relationship quickly turned sour. Marketing people and accountants from Jupiler bombarded Pierre with demands to make his beer more quickly, using cheaper materials.

He gave up, sold the brewery to InBev and moved to Texas, where he opened a brewery and launched Celis White. When he returned home, he discovered that InBev had taken the catastrophic decision to close the Hoegaarden brewery in 2006 and transfer production to the Jupiler plant near Liège. It was doubly insulting to the people of Hoegaarden: their much-loved beer was moving to a lager factory in a French-speaking area. The move proved a disaster. The quality of the beer plummeted along with its sales and reputation, and Inbev rushed back to Hoegaarden, its tale between its legs.

Today, as you drive into Hoegaarden from Leuven, you are confronted by a vast, sprawling complex of warehouses with delivery trucks branded with Stella, Jupiler, Leffe and just about every Belgian beer owned by the colossus AB InBev, the result of the merger between Ambev of Brazil, Anheuser-Busch of the U.S. and InBev. The Hoegaarden brewery is working again but it’s dwarfed by the big brands of the owning group.

But traditional brewing has not been lost. By coincidence, just as InBev was planning to close the Hoegaarden plant, Jan De Wachter and Mieke De Backer started to brew in their cafe, Nieuwhuys, on Ernest Ourystraat. The spacious cafe has bare brick walls, beamed ceilings and tiled floors, with a large back room for live music and a massive bar fronting the street serving a large range of beers. The original bar burnt down – Hoegaarden seems singularly unfortunate with fires – and even though the current building dates from 1636 it’s called the New House or Nieuwhuys.

Pierre Celis had a strong attachment to Nieuwhuys as it was the first cafe in the town to sell his beer when he started his brewery. He was happy to advise Jan and Mieke and told them firmly they had to make a white, spiced wheat beer or they couldn’t be true Hoegaarden brewers. They had started with a dark beer and added both an amber and a blond, as they wanted to have distinctive beers in a town dominated and overshadowed by the Hoegaarden plant. But out of deference and respect to Pierre – who died in 2011 aged 86 – they produce a white beer as a summer-time seasonal.

Jan worked as an engineer in South Africa for several years and, despairing of the quality of the beer there, started to brew at home. When he returned to Hoegaarden he smelt brewing in the town and got the urge to brew himself. Mieke was also steeped in the brewing background of Hoegaarden and, after working in a shop in Poperinge, she took over the Nieuwhuys. She had met Jan in Brussels and they joined forces in the cafe. Both did a one-year brewing course in Anderlecht.

Their beers were so well received that they have moved a few yards from the cafe and built a new brewery with greater capacity. They have added a second fermenting vessel and sell beer in Leuven as well as Hoegaarden. Their fortunes were aided in 2012 when they won the dark beer class in the International Beer Challenge.

In the style of small Belgian breweries, the mash vessel doubles as the boiling kettle. When the mash is made, it’s filtered in a small lauter tuns then the filtered wort is returned to the first vessel for the boil with hops. Four malts are used, depending on the recipe, and are supplied by Weyermann in Bamberg. Hops in pellet form come from the main Belgian growing area around Poperinge.

The warm-fermented beers are conditioned for two or three weeks then given a dosage of brewing sugar to encourage re-fermentation in bottle or keg. Jan and Mieke use several different yeast cultures supplied by the Kroon research brewery run by Professor Freddy Delvaux, who started his own business after running the acclaimed brewing faculty at Leuven University.

The two main beers are Alpaide and Alpaide Blond, named in honour of the Countess Alpaide or Alpaidis, who lived in the Hoegaarden area around the year 900 and donated land to Liége when she died. The dark version is 10% and brewed with pale and roasted malts, caramalt and wheat. The hops are Saaz and East Kent Goldings. The beer has a big roasted malt aroma with a punch of caramel reminiscent of a Mars Bar, the rich grain notes balanced by peppery hops. Creamy dark grain, caramel, burnt fruit and peppery hops fill the mouth, followed by a long, dry finish rich in dark fruit, roasted grain and bitter hops.

Alpaide Blond is 8.5% and carries the tag line “cuvé van de generaal”. There’s a military base in the area and the colonel of the regiment drank in the Nieuwhuys and asked Jan and Mieke to brew a blond, as his favourite beer was Westmalle Tripel. The brewers responded and launched it to coincide with the colonel’s promotion to general. The beer is brewed with pale malt and wheat, with East Kent Goldings and Saaz hops. It has spicy hop resins and creamy malt on the nose, with tart fruit in the mouth balanced by creamy malt and tangy hop resins. The finish has tart fruit, bitter hops and a cookie-like malt note.

An amber beer is called Rosdel, the name of a local nature reserve. It’s 6% and is brewed with pale malt, roasted malt, caramalt and Munich malt. The hops are Cascade and Magnum. It has a rich aroma of caramel, chocolate, dark fruit, roasted grain and floral hops. Hops build in the mouth, balanced by roasted grain and chocolate, followed by a quenching finish with juicy and creamy malt, dark fruit and bitter hop resins.

Jan and Mieke are making more than beer. Outside the brewhouse, there’s a small distilling unit when they are making geneva and they plan to make other spirits, too. In Hoegaarden, AB InBev aren’t under threat but they’re facing a taste test.

*www.nieuwhuys.be. Brewery visits are available on Saturdays. Image of a brewery truck in the early 20th century shows that French was still the dominant language