Pale ale and the long voyage to India

Added: Sunday, January 28th 2024

By Des de Moor

Poor Pete Brown. When the beer writer tried to recreate the journey of a 19th century India Pale Ale from Burton upon Trent to Kolkata in 2008, he and Steve Wellington, the renowned ex-Bass brewer who was then running Burton’s Museum Brewery, assumed it would have been a cask beer and made it that way. It was only afterwards that Pete began digging in earnest into historical sources, reading in William Tizard’s The Theory and Practice of Brewing, first published in 1848, that IPAs for export were prepared quite differently. In Hops and Glory, the 2009 book that resulted from the experiment, Pete notes that ‘true IPA was not technically real ale. And that means that Steve Wellington and I had packaged our beer wrong, following a tradition that wasn’t even invented in IPA’s heyday.’ As if to prove the point, one of Pete and Steve’s pins exploded long before reaching the Indian Ocean.

I recounted this story and included the quote, admittedly approvingly, in my 2023 book Cask: The real story of Britain’s unique beer culture, which may be why our esteemed host Roger Protz wrote in his review that ‘It’s disappointing to find that Des de Moor repeats the urban myth that IPA “was not technically real ale”’. Which I guess serves me right for not being sufficiently rigorous in my terminology, even when I’m quoting others. I’m only too aware how slippery our beer terms are, particularly if we attempt to impose them uncritically on the brewing practices of the past, and I spent quite a few paragraphs in the book trying to unpick some of the resulting conundrums.

Whether or not early export IPAs were ‘real ale’ or not depends what you understand by the term. If you mean what CAMRA now more precisely calls ‘live beer’ after updating its definitions in 2020, a beer that still contains sufficient yeast and sugar to continue to ferment in the vessel from which it’s finally dispensed, then early IPAs would certainly qualify. As Roger rightly points out in his review, the carbon dioxide produced by active fermentation had to be managed carefully during shipping using porous venting plugs (spiles), casks had to be extra-strong to withstand the pressure and the beer threw a generous sediment. But if by ‘real ale’ you mean the sort of fresh, clean-tasting cask beer we enjoy in pubs today, then a close study of how those original IPAs were made and how they evolved suggests they were a rather different product with a distinct flavour profile, emerging from a much older tradition of brewing.

Typical modern cask beers are designed to be brewed and drunk quickly: they're fermented in around a week then given perhpas a few days at the brewery and in the pub cellar to "condition" or recarbonate, through renewed yeast activity. And once you start emptying the casks, the beer will only remain drinkable for a few days more. Cask haa one of the most rapid turnarounds known to commercial brewing: a beer might be on sale at a taproom or nearby pub in as little as 10 days after it was brewed. The resulting beer, at its best, is praised for its freshness and relatively clean flavours, often offset by a dash of the fruity esters which British brewers' yeast tends to leave behind.

The old India Pale Ales, in contrast, spent much longer in storage before they were considered drinkable, as did the original porters and stouts, matured for many months and sometimes even years in wood. They inevitably underwent what we now call a ‘mixed fermentation’, involving a much more diverse population of yeasts and various bacteria too. This yielded a more complex flavour profile, with a dash of sourness and spicy, ‘funky’ and animal-like wild yeast characteristics.

Ageing beer became common practice following the widespread adoption of hops in English brewing in the 16th century. Hop acids, alcohol and increased acidity all have a preservative effect, deterring unwanted infections. Making a strong beer with plenty of hops then ageing it for extended periods resulted in a more stable, long-lasting product. Treated thus, it lasted far beyond the shelf life of the ingredients it was made with, and certainly long enough to ensure drinkable beer was available all year round, even in the warmer months when, in the days before artificial cooling and refrigeration, successful brewing was highly challenging if not impossible. The weaker ‘small’ beers of the day, in contrast, would only remain palatable for two or three days after fermentation completed.

Aged pale ales were regularly brewed on country estates, important centres of non-commercial brewing since medieval times and highly influential on the large-scale commercial industry that emerged from the 18th century. The most celebrated country house beers were known as ‘October ales’, so-called because they were brewed in that month, soon after the harvest, and laid down in wooden casks for at least a winter or a summer, with some being kept a decade or more. A brewing manual written in the 1730s suggests managing them by keeping them bunged until spring, releasing the bung in the summer to allow for further fermentation, then rebunging them in the autumn.

To understand what’s going on here, we need to dig a little deeper into the science of fermentation (not that this was understood at the time). Alcoholic fermentation in beer involves yeast, a single-celled fungus, breaking down dissolved sugars created from grain starch and converting them to alcohol and carbon dioxide (CO2), the latter giving the beer its sparkle. But wort, the sweet liquid that results from the malting and brewing processes, contains various types of sugar and other carbohydrates, classified according to their molecular complexity. And there are numerous different species of yeast, each with its own capabilities for fermenting different types of sugar.

Common brewer’s yeasts from the genus Saccharomyces, the sort the brewer deliberately adds to the wort, readily consume the simplest sugars, like glucose and maltose, near-exhausting the supply within a few days. But they can’t tackle the more complex ones, known as dextrins. However, many other yeasts live wild in breweries, and particularly in the nooks and crannies of wooden vessels, which are impossible to sanitise thoroughly even today. They include members of the genus Brettanomyces, or Brett, which can digest complex sugars other yeasts leave on the side of their plates, but are more leisurely about it, taking weeks and even months. By now, air will be seeping through the porous wood, but Brett is also happier at fermenting in the presence of oxygen than brewer’s yeast.

Oxygen itself produces flavour changes, lending musty, sherry-like notes, and facilitates other micro-organisms lurking in the environment, particularly bacteria which produce sour-tasting lactic and acetic acids through different kinds of fermentation. And the various flavour compounds undergo chemical changes over time, with more aggressive flavours and aromas rounding off and mellowing out. All this is familiar to aficionados of modern wild and mixed fermentation beers, like traditional Belgian lambics and sour brown ales and the modern craft beers inspired by them. Today these are regarded as niche specialities, and few people realise that beers like them were part of mainstream brewing until relatively recently.

Until the 1930s, brewers reserved the term ‘secondary fermentation’ for the sort of complex mixed fermentation that takes place in aged beers, though by then the process had almost completely disappeared from English brewing. As I explain in my book, its importance had begun to decline in the first half of the 19th century as public tastes shifted from sour and vinous ‘stale’ vatted porters towards young, fresh tasting ‘mild’ ales, the ancestors of today’s classic cask styles. These were rapidly carbonated, or conditioned, in the cask with the same strain of yeast used to ferment them and intended to be drunk long before Brett and acid bacteria had a chance to make their presence felt. As the old sort of secondary fermentation disappeared, brewers and, later, beer campaigners re-applied the term to the more familiar process of cask conditioning, laying traps for unwary historians.

India Pale Ale, as Roger recounts in his 2017 book IPA: A Legend in our Time, developed as a commercial variant of the fine pale ales produced in country houses, generously endowed with alcohol and hop acids to enhance its ageing potential. Famously, the sea voyage seemed to accelerate the process of maturation, so the beer reached its peak more quickly than if left to languish in an English cellar. But even so it needed further maturation after arrival in India before it was considered fit to drink. Undoubtedly it acquired its sublime state through a secondary fermentation in the old sense, involving various species of yeast, bacteria and the chemical effects of oxidation and ageing.

This is supported by accounts of how beers were prepared for export. The major hazard here was that the pressure of CO2 from ongoing fermentation got so high that it burst the casks in transit. Brewers took precautions not only by strengthening the casks but ensuring that the brewer’s yeast had used up nearly all the fermentable sugar, separating out as many of the yeast solids as possible and leaving the beer in open vessels to go flat before packaging. By journey’s end it was once again carbonated, which must have been through the action of wild yeasts on more complex sugars.

Not everyone agrees with this view. An influential 1994 article by US brewer and brewing historian Thom Tomlinson, quoted in Roger’s book, claims that Hodgson’s, the brewery most celebrated for exporting strong pale ale to India in the early 19th century, ‘heavily primed’ its IPA, and that the Burton brewers treated their export pale ales with ‘high rates of priming sugar’. Priming is when refined fermentable sugar is added during packaging, reinvigorating the brewer’s yeast to ensure healthy conditioning, a technique often, though by no means always, used today with cask conditioned beer. If IPA for export was primed, its conditioning would more closely resemble modern cask, likely followed by at least some wild fermentation.

Tom doesn’t give a source, and I wonder if he simply assumed the beer must have been primed without giving due consideration to the powers of wild yeast. Numerous accounts stress the need to ensure all yeast activity has ceased before packaging, so going to all this trouble only to shock the yeast awake again with sugar seems counterintuitive. Adding sugar to beer in this way was in any case illegal in England between 1802 and 1880. A Bass chemist told a parliamentary committee in 1899 that, though by then Bass was regularly priming everyday beer to accelerate its maturation, for ‘the export and strong ale, No 1 as we call it, and other varieties of strong beer that have to be kept some time, there is no necessity to use the priming’.

Sadly, nobody took much in the way of tasting notes prior to the 1970s, but we can assume these old IPAs tasted rather different both from the cask pale ales and revived craft IPAs of today. For a start they would have exhibited the telltale notes of wild yeast, as Roger himself found tasting his Catalyst IPA, his attempt at recreating the style in collaboration with Stu Sewell at UBREW in Bermondsey in 2016, after four months in a wooden cask and a month in bottle.

An accomplished brewer with an interest in historic styles once insisted to me that classic IPAs couldn’t have undergone a mixed fermentation because they would have been too pungent and therefore wouldn’t have been regarded with the same reverence. But I think he was underestimating the way flavour compounds mellow with further age. While Brett notes in relatively young beers can be forthrightly goaty, mouse, wet dog, horse blanket or whatever other animals you care to evoke, given a few months they can evolve into intoxicating fruit and perfume notes, as in mature unblended lambics, or that bottle of Orval that’s been at the back of the cupboard for a while.

And, despite their well-documented generous hop additions, those old IPAs likely weren’t anywhere near as hop forward as most people assume. This was not just because older varieties contained lower concentrations of bitter acids than today’s ‘high alpha’ hops. Hop aroma rapidly disperses, which is why so many contemporary brewers advise you to drink their beers fresh, and hop bitterness eventually rounds out too. Brewers used hops in beers intended to age primarily for their preservative qualities, secure in the knowledge that the inevitable bitterness would dwindle to palatable levels by the time they were drunk. Some of the few notes on beer flavour we have from the early 19th century confirm that ‘mild’ beers had more pronounced bitterness than ‘stale’ ones, even though fewer hops were added to them.

That’s not to say there’s anything wrong with modern IPAs: they’re an important style in their own right which has helped transform the way we think about beer and provided a massive boost both to craft brewing and discerning drinking. The people who pioneered the IPA revival in the late 1970s and 1980s on the assumption that they were recreating rather than reinventing something can’t be blamed for not fully understanding the history, given the state of beer knowledge at the time. But I’d love to see more brewers trying their hand at faithful recreations from the more informed perspective of today, as Roger and Stu did with Catalyst. There are a few around, and I jump at the chance to try them.

So to summarise: saying IPA wasn’t technically real ale isn’t repeating an urban myth, though it’s not telling the whole truth. IPA was a live beer, but it was very different from today’s cask. This might seem simple quibbling over terms, but getting history right matters. The received wisdom about beer is often hampered with notions of ‘tradition’, and cask beer advocates are particularly prone to touting their favourite tipple as an unbroken link to a halcyon past. But brewing is a complex and evolving art, and today’s cask beer is as much a result of scientific, technological and economic innovation as any other product, representing a break from a past where they did things rather differently.

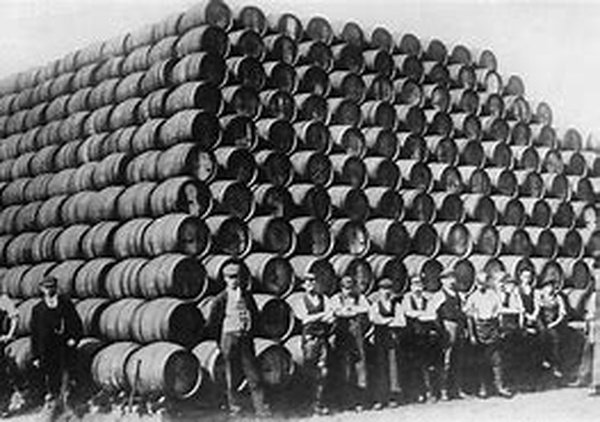

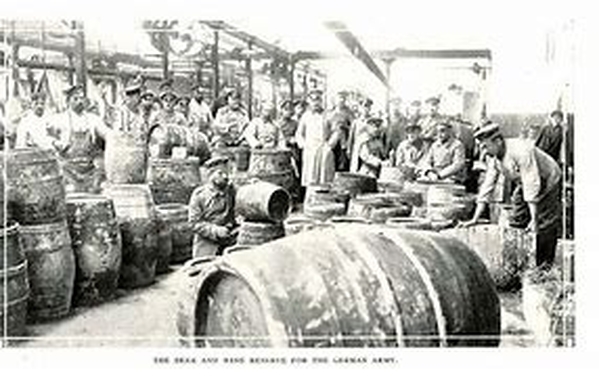

Images from top: sailing clipper from London to India; casks stored at Burton prior to shipping; casks unloaded in India; casks being prepared for loading in British docks