Tall tales from England's highest pub

Added: Wednesday, October 16th 2013

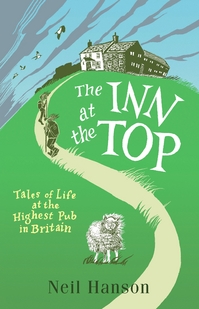

The Inn at the Top by Neil Hanson (Michael O’Mara Books, £8.99)

Two things can be said without contradiction if you read this book: you will never want to run a pub and you will keep well clear of the more remote parts in Yorkshire in the winter. Neil Hanson, who went on to edit the Good Beer Guide and then became a successful writer of history and travel books, ran with his wife Sue the highest pub in England in the 1970s. It’s just called the Inn at the Top here but it’s famous under its true name of the Tann Hill Inn.

The pub stands 1,732 feet above sea level in Swaledale. It had a reputation for being cut off by snow in winter and for the rapid turnover of people prepared to run the place. When the Hansons arrived, it was a different age. As Neil says, “In that year of our Lord 1978, the ‘Winter of Discontent’ was just a lowering cloud on the horizon, Jim Callaghan was prime minister, the Yorkshire Ripper was still at large, and the leader of the opposition was the ‘Grantham Ripper’, Margaret Thatcher, also known as ‘the Iron Lady’ and ‘Attila the Hen’.”

The title of the opening chapter – Even Heathcliff Wouldn’t Live Up Here – sets the tone. At the time, the pub was owned by a couple of wide boys from Tyneside called Neville and Stan who spent minimal money on the upkeep of the buildings. The cheapest material had been used for repairs and as a result the roof leaked and Neil spent an inordinate amount of time every day firing up boilers to keep the pub warm – a necessity all year round – and supplying hot water to the kitchen and bedrooms.

And then there were the rats...Neil and Sue got rid of the blighters when they arrived but they did have a habit of returning and making their presence felt when the bar was packed with customers.

Trade was divided fairly equally between the “locals” and visitors. “Locals” is placed in quote marks because some of the regulars lived considerable distances from the pub, the only licensed premises for miles around. They were mainly sheep farmers, many of whom had never left the dale, and greeted “incomers” with well-honed hostility. Like their sheep, they were inbred and many of their sons lived in mortal terror of the opposite sex.

They regarded the inn as their private place and gave scant regard to official licensing hours, which were then heavily restricted. Fortunately for the Hansons, the police rarely visited the inn. The local constabulary was well aware of drink being served after hours but turned a blind eye. Neil got no thanks from the locals for bending the law and serving “lates”. He was a dreaded incomer and was treated as an outsider for months. One of the first questions put to him by a farmer was “Nah then, lad, dost tha ken Swardle yows?” When Neil scratched his head, the farmer grunted “thought not” and joined his friends at their table. It was Neil’s introduction to the local impenetrable dialect and the vital role played by sheep in the area: Swardle is the local name for the Swaledale breed.

Regulars arrived by foot, car and bike. Some had to improvise. Every day, an ancient woman called Faith hitched a lift in the back of the Post Office van. She would arrive at the inn, drink several whiskies and sodas, chain smoke strong cigarettes and then return to her cottage with a supply of bottled Guinness.

Inevitably, the inn was cut off in winter, especially the cruel one of 1979. Snow drifts were packed around the inn and those trapped inside either stayed in their bedrooms, if they’d booked, or slept on the pub floor. The boilers packed up, the beer ran out and supplies of whisky and wine ran dangerously low.

The Inn at the Top is a warm, amusing and at times sad book – for many of the regulars, on their remote farms, led miserable lives. It’s also beautifully written: Neil speaks of the grumpy nature of some of his customers and admits: “My own irrational rages were mainly sparked by the unreasonable demands of the sort of pernickety customers who would have sent the wine back after the Miracle of Canaa because it wasn’t chilled enough or, faced with the miracle of the loaves and fishes, would have complained that it was only a two-course lunch.”

Neil and Sue eventually gave up and moved away though the pull of the pub is clearly still strong some 35 years later. The inn is still in business – though this may not be the best time of year to visit it.