Historic Hooky is set for the future

Added: Thursday, July 19th 2018

Whenever I visit the Hook Norton Brewery, I’m reminded of that old Gene Kelly musical Brigadoon about a Scottish Highland village that mysteriously appears for only one day every 100 years.

The brewery is an equally magical experience. To find it you drive through the picture postcard village of Hook Norton in Oxfordshire – all winding cobbled streets and half-timbered thatched cottages – until you find the Pear Tree Inn.

You turn up Brewery Lane and suddenly out of a mist of steam and inviting aromas of malt and hops you are confronted by one of the enduring and inspiring visions of brewery architecture, the Victorian tower brewery of Hook Norton.

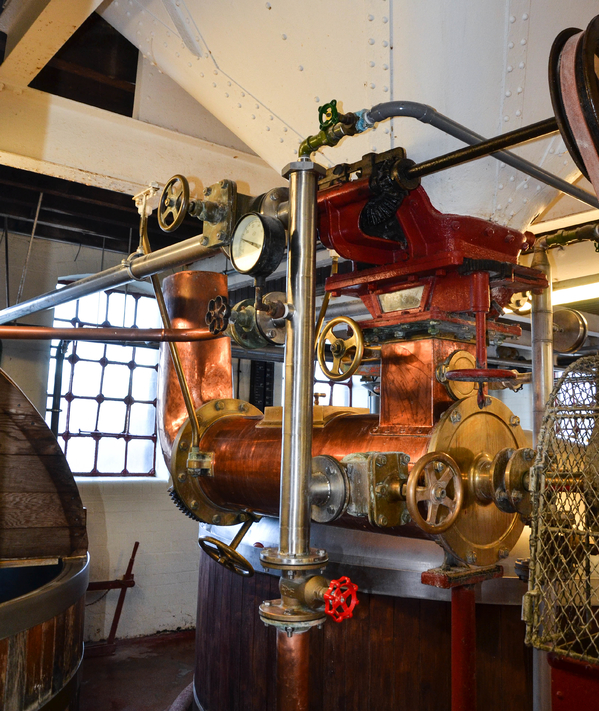

The brewery dates from 1849 and was built by a farmer, John Harris, to refresh both farm labourers and the small army of navvies building the railway line that ran past the village – the line has long gone. The present brewery buildings opened in 1900 and visitors can revel in the splendours of an old steam engine and oak-lined mash tuns and coppers (pictured below).

The Grade II-listed brewery was designed by William Bradford who also drew the plans for Harvey’s of Lewes and Tolly Cobbold of Ipswich. They’re called tower breweries as the brewing process flows logically from floor to floor by gravity, removing the need for pumps.

As I approached the brewery on my most recent visit, dead on cue the Hook Norton brewery dray appeared with a driver in traditional garb that includes a bowler hat. The delivery that day was being made to the Pear Tree down the lane, scarcely an arduous trip, but the four dray horses stabled on site can travel further, taking beer to some of Hook Norton’s 35 mainly rural pubs.

While the brewery is firmly rooted in its rich history, it’s not living in the past. James Clarke, the managing director (pictured), is a member of the founding family and has worked at the brewery for 27 years. He became head brewer in 1998 and then MD following the death of his father.

He is busily expanding the business, not only developing a range of new beers but also offering facilities for visitors to tour the site, eat in an elegant dining room called the Malthouse Kitchen and also -- if the fancy takes them -- brew their own beer on a 3½ barrel pilot plant.

“We’ve spent £150,000 developing the restaurant with a fully fitted kitchen,” he says, “and we’re planning to get a licence for weddings to be held at the brewery.

“The visitor centre and tours are doing well – our provenance is important to the business. We’re also investing in our pubs to improve the quality of both food and drink.”

The biggest change is the beer range. For years, the brewery produced mild, bitter and the premium Old Hooky. But now James and his team are creating 50 to 60 different beers a year. They’re not all regular brews. New beers are trialled on the pilot plant and if customers like them they become regular or seasonal members of the portfolio. Cotswold Pale is a case in point.

Hook Norton’s production of 15,000 barrels a year is split 75 per cent draught and 25 per cent bottle. Keg now accounts for 5 per cent of draught and James says that will grow as a result of demand from publicans.

“Cask beer is the best drink in the world when it’s right,” he says. “But there are too many brands today and that leads to slower throughput, wrong temperatures and poor hygiene. The quality of cask beer needs focus and attention.”

To help with that focus, the recently created Balm Cellar holds regular training sessions to improve cellar and bar skills for publicans: barm is a brewers’ term for yeast.

The demand for keg beer comes from Hook Norton’s own pubs, which account for 15 per cent of sales, along with the free trade: the brewery delivers within a 50 mile radius. While the majority of pubs are in rural settings, Hook Norton has a showplace outlet in Oxford, the Castle. It offers the brewery’s cask and keg range along with guests from the likes of Tiny Rebel and XT as well as the famous Czech lager Pilsner Urquell.

James smiles if you mention the big debate over the merits of cask and keg and what constitutes “craft beer”. He thinks that’s a metropolitan discussion among the chattering classes.

“The country is different to the town,” he says. “People who go our pubs won’t sip a few halves – they will have several pints.”

Drinkers can choose from a permanent cask range of Hooky Mild, Hooky Bitter, Hooky Gold and Old Hooky with the superb Double Stout among the monthly seasonal range. Keg beers include Cotswold Pale, Red Rye and a Black IPA.

James says he has noticed a growing interest in darker beers, which encourages him to stay true to Hooky Mild. It accounts for just 5 per cent of annual production but he says it remains a core brand.

“At 2.8 per cent, it’s a good lunchtime drink,” he points out.

The cask ales are brewed – as they have been for decades – with Maris Otter pale malt and Challenger, Fuggles and Goldings hops. They have been joined in recent years by 15 different malts and hops from Germany, New Zealand and the United States.

James is keen to build his relationship with beer drinkers. As well as brewery tours, members of the public can become brewers for a day and use the pilot plant to fashion their own beers.

“They get two nine-gallon firkins to take home when the beer is ready,” he says. They have to work hard for their beers, he adds, as they have to shovel the spent grain out of the mash tun when the brew is finished.

Hook Norton is well set for the future. As well as 50 staff, James employs his two sons, one in the brewery, the second in a pub in Banbury.

The dynasty will endure and James is determined to produce beers for a wide and discriminating audience.

“We’ve got to celebrate the diversity of beer,” he says. “We’re 20 years behind the wine industry.”

But it’s catching up fast, thanks to the efforts of breweries such as Hook Norton. As I drive back down Brewery Lane I glance behind me. Already the old tower brewery is beginning to fade in the steam generated by the brew house. But I fancy, like Brigadoon, it will still be there in 100 years’ time.

*www.hooky.co.uk. The Castle, 24 Castle Street, Oxford.