Mild: it's not as dead as the Dodo

Added: Wednesday, May 13th 2015

Tony Naylor’s article on the demise of Mild Ale in the Guardian Online on 9 May brought to mind the famous Mark Twain aphorism: “Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated”. Naylor’s peg for the piece was the decision by Robinson’s brewery to stop production of its Mild, news that prompted a curious and twisted piece of logic on the writer’s part.

“If CAMRA ever needed a reminder of the task it faces – saving traditional beer from extinction – it got it when Manchester brewery Robinson’s announced on 30 April it was ending production of its 1892 Mild – just as CAMRA kicks off May Mild Month, its annual rearguard action in defence of this most meek of beer styles.”

I know that “journalism” and “standards” are often unlikely bed fellows these days but I still happen to believe that some basic research is sensible before bursting into print.

Naylor begins with the astonishing suggestion that CAMRA is attempting to save traditional beer from extinction. All the statistics – including the annual Cask Report, produced independently of the campaign – shows that cask beer is enjoying a remarkable renaissance. Since the current Good Beer Guide was published last September, 128 new breweries have opened. Not all the beer brewed by independent British brewers comes in cask form, but the bulk of it does. I suspect – recalling another Guardian piece by Tony Naylor a few months ago – he has built a dividing wall between cask beer and craft keg. It’s a wall I’m keen to kick down: good beer is good beer, regardless of the container it comes from.

Where Mild is concerned, it’s down but far from out. The volumes of Mild sold in Britain are a fraction of those enjoyed by the style decades ago. But beer lovers should be concerned with quality not quantity. The French drink more standard wine than vintage ones – should growers stop making vintages? Whisky drinkers consume more blends that single malts – should producers stop making single malts?

And Mild is making a spirited comeback. Today there are 230 Mild Ales brewed in Britain, twice the number compared to 2000. Perhaps Tony Naylor’s derided Mild Month by CAMRA has had an impact. The decision by Robinson’s is disappointing but the Stockport brewery is not typical of the rest of the industry. It has recently installed a modern brewhouse that’s not geared to producing short-run beers. Smaller brewers can be more flexible.

But it’s not only small brewers who remain committed to Mild. Greene King, which produces around 250,000 barrels of beer a year, continues to make its XX Mild and has written to 2,000 of its publicans urging them to stock the beer during May.

Banks’s in Wolverhampton, part of the Marston’s group, claims to be the biggest brewer of Mild Ale in the world. Banks’s Bitter has now overtaken sales of Mild but the dark beer continues to be the brewery’s biggest seller in the West Midlands. Banks’s has an annual capacity of 100,000 barrels and is producing a large amount of Mild: sales of Bitter and Mild split 60-40.

Throughout the country, brewers has responded to CAMRA’s May boost for Mild by promoting their versions of the style. Castle Rock in Nottingham is stocking at least one Mild in its pubs, spearheaded by its 3.8% Black Gold. The strength of Black Gold should give Tony Naylor pause for thought. He describes Mild as “this most meek of beer styles” but it’s a misunderstanding of the style to assume to it has to be low in alcohol.

Mild Ale came to popularity in the early 19th century. The name stems from the fact that unlike porter and stout it wasn’t aged for long periods but was brewed for quick consumption. It therefore lacked the acidic character of porter and stout, and was sweeter – which coincided with the growing popularity of sweeter food and drink at the time. Mild was less heavily hopped than other beers but it certainly didn’t lack hop character.

At the turn of the 20th century, the average strength of beer was around 6.5% and by that time Mild had become the most popular beer style in Britain and remained so until the 1950s. In common with all beers, including IPA, the strength of Mild was drastically reduced during World War One as a result of much heavier rates of duty imposed on brewers by the government.

The survival of the redoubtable Sarah Hughes’ Dark Ruby Mild at 6% shows that a true, traditional Mild can be high in alcohol. They can also be well-hopped. Joseph Holt’s Mild in Manchester is only 3.2% but has 32 units of bitters, high for the style. The keg version of Holt's Mild, called Dark, is sold in all its managed houses, with the cask version available in 15% of the pubs.

Rudgate Brewery’s Ruby Mild was named Champion Beer of Britain in 2009 and weighs in at 4.4% -- stronger than many Bitters.

We need to cherish and nurture our great beer styles, not deride and dismiss them. No other country brews Mild Ale. Belgium and the United States have Brown beers but they are quite different in character. The success of revivalist Porters and Stouts is proof that people will drink dark beers and Mild may yet have its day again. Simon Yates, assistant head brewer at Banks’s (top picture), believes so. “I think Mild beer will be rediscovered,” he told the Wolverhampton Express & Star. “It’s a fuller flavoured, easy drink. Mild has a distinct malty flavour.”

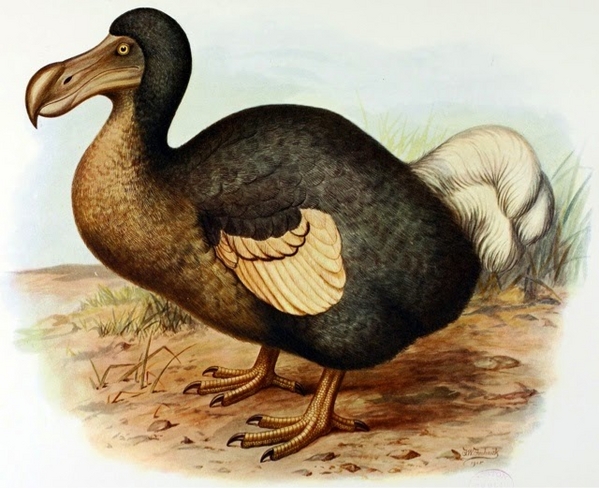

Robinson’s decision to call its Mild “1892” may not have helped give it modern consumer appeal. Let’s have more imaginative names for Mild. But please don’t call it Dodo.