40 years on, Big Beer still rules the roost

Added: Friday, August 24th 2018

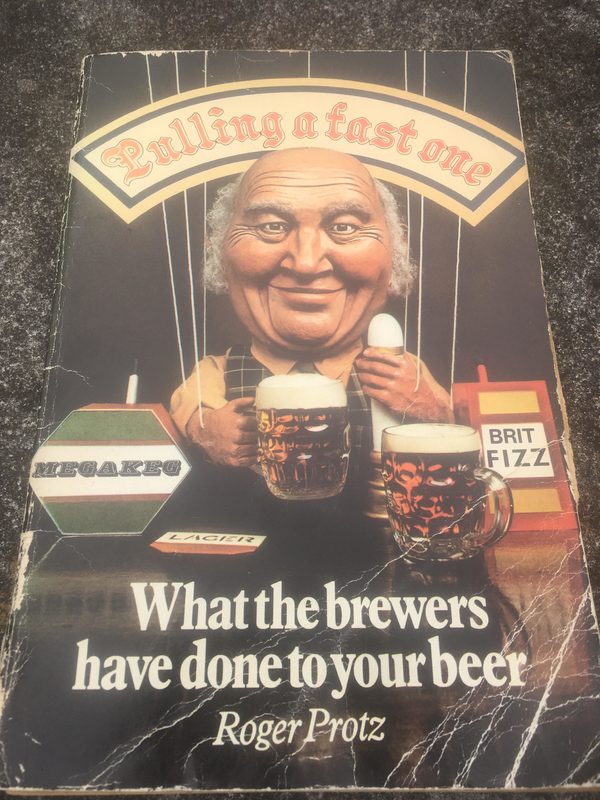

A sudden interest on Twitter about my first book sent me scurrying to the bookshelves to find a dog-eared copy. It’s called Pulling a Fast One: What the Brewers Have Done to Your Beer and it was published in 1978.

Flicking through the pages reminded me of the old French expression: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose – the more things change, the more they stay the same.

The book is a critique of the tactics of the big brewers of the day and if you replace national brewers with global versions and add on the role of giant pub companies, the message is clear: the punter is still being screwed today.

I was taking aim and what was called the Big Six. They were made up of Allied Breweries (Ansells, Ind Coope and Tetley), Bass Charrington, Courage, Scottish & Newcastle, Watney Mann & Truman, and Whitbread. Bass was the biggest brewer at the time. I described S&N as “not well known outside Scotland and the North-east.” Today it’s the only survivor of the Big Six and is Britain’s biggest brewer under the name of Heineken UK.

It’s fascinating to see the cover concentrates on keg beer, with just a small beer mat labelled “lager”. Eurofizz was then in its infancy.

The book opens with a quote from a reporter on the South Wales Echo, written in October 1977: “Just look at the breweries South Wales has lost over the years...There were the Taff Vale and Giles and Harrop which kept the Merthyr Tydfil areas bubbling. Over the mountain the Black Lion slaked the thirsts of Aberdare. Then we had Evan Evans Bevan rolling out the barrels at Neath and in Mid-Glamorgan the Bridgend Brewery was kept busy keeping everyone’s pints foaming. Also in a glass of their own at Cardiff were the redoubtable Hancocks and Ely breweries. Sparkling up at Aberbeeg were Webb’s, while Phillipps and Lloyd and Yorath of Newport kept a cool head in South Gwent. Now Brains of Cardiff, Felinfoel Ales and Buckleys of Llanelli are the sole remaining independent brews left in South Wales.”

It was the same picture in all parts of Britain. I said: “In less than 20 years it [brewing] has been transformed from an industry where several hundred regional companies produced a wide range of beers to suit every palate to an industry where six conglomerates dominate more than 80 per cent of production and supply.”

The transformation was remarkable. Until the 1960s, Britain had no national brewers. Bass, based in Burton-on-Trent, had a national reach as Draught Bass was a required beer in many other breweries’ pubs, but the likes of Watney and Whitbread were just large regional companies. It all changed when a Canadian called Eddie Taylor wanted to turn Carling Black Label into a national brand in Britain. To do that, he needed breweries and pubs throughout the country. He went on a buying spree, eventually ending up with a group called Bass Charrington that spread from Tennents in Scotland to Charrington in London. The group controlled 20 per cent of the brewing industry, owned 10,000 tied outlets and had an annual turnover of £900 million.

The other big regionals were frightened out of their skins and went into overdrive to follow Bass. CAMRA once had a T-shirt labelled the “Whitbread Tour of Destruction” that listed the breweries it had taken over and closed down. They included such famous and well-loved companies as Fremlins, Tamplins, Lacons, Flowers, Starkey, Knight and Ford, Castle Eden, Chesters, Brickwoods, Strongs and – mention it quietly in Scotland where the closure still bears scars – Campbell, Hope and King.

Watney followed a similar course. It became Watney Mann by merging with Mann Crossman and Paulin. It went national, buying and swallowing Wilsons of Manchester, Phipps of Northampton, Ushers of Trowbridge, Drybrough in Edinburgh and Ballards and Steward & Patteson in Norwich. Watney Mann was later bought by the Grand Metropolitan leisure group and merged with another London brewer, Truman.

By 1977 the market share of the top seven companies – the Big Six plus Guinness, which owned no pubs and then had a brewery in London – stood at 89 per cent of brewing and distribution. The remaining 11 per cent was shared by 87 other smaller brewers. Nine out of 10 pints of beer brewed in the UK were brewed by the national combines.

And beer was changing. The Big Six couldn’t be bothered with fussy cask-conditioned ale that had a short “shelf life” of just a few days. The national brewers, aided by the new motorway system, needed beers they could trunk all round the country and which would stay in drinkable condition for weeks and even months.

Enter keg beer. It’s important to stress that the major keg brands of the 1970s and 80s bear little comparison to modern craft keg brews. The likes of Watney’s Red, Bass’s Worthington E, Courage Tavern, Whitbread Tankard, S&N’s Tartan and Allied’s Double Diamond (rumoured to be the Duke of Edinburgh's favourite beer!) were truly horrific. I once described Watney’s Red as tasting like liquid Mars Bars and it fitted the other major kegs: sweet, glutinous and hiccup-inducing gassiness.

The beers were foisted on an unsuspecting public. When Watney took over Tamplins of Brighton and Henty and Constable of Chichester the company replaced the two distinctive bitters produced by those breweries with a new beer called Sussex Bitter. But this was withdrawn in 1970 and replaced by a national brand, Watney’s Special.

The company followed a similar course in Norfolk. It bought and closed Bullards and Steward and Patteson and replaced their beers with one called Norwich Bitter, brewed at the city’s remaining brewery, Morgan’s. When Watney closed Morgan’s, “Norwich Bitter” was transferred to the former Phipps brewery in Northampton.

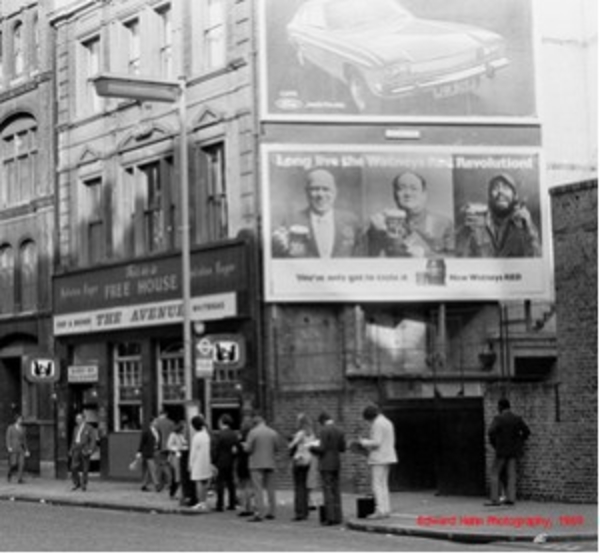

One after another, local and regional beers were replaced by national brands. Between 1966 and 1976, the number of beer brands in Britain fell from 3,000 to less than 1,500. The national brewers claimed the decline in the number of regional beers was due to consumers preferring the new keg beers. But this preference was due to the fact that many of the old regional brews were no longer available and keg beers were massively promoted on television, in the press and on billboards.

There was an infamous and risible billboard in the late 1970s (pictured above) for Watney’s Red showing lookalikes for Fidel Castro, Chairman Mao and Nikita Khrushchev drinking the noxious beverage with the slogan “the Red Revolution”. It was laughed to scorn by young radicals of the time.

In 1977, more than £20 million was spent on advertising beer and almost all that sum was devoted to keg and lager. When the national brewers spoke of “demand” for their keg brands, they actually meant arm-twisting. In that year, Bass spent £310,000 promoting Worthington E, with sentimental commercials showing men going off to fight in the Great War singing “Daisy, Daisy”. When I asked a Bass publicity spokesman why his company spent more on promoting Worthington E than Draught Bass he replied: “Because we sell four times as much E as Bass.” It was not surprising. In 1977 Bass spent scarcely a penny on Draught Bass, even thought it called it “one of the great ales of old England.”

There is one clear link between the 1970s and today’s beer scene. The big brewers, then and now, charge more for their products than small independents and, then and now, work the old dodge of decreasing the strengths of their brews in order to pay less excise duty. For example, in 1960 Worthington E had an original gravity of 1041.8. By 1971 it had fallen to 1036.8. In the same period, Ansells Bitter had fallen from 1045.3 to 1038.9.

In 1977 the Price Commission was asked by the government to report on beer prices and in particular to look at the prices charged by the national brewers. The commission’s findings were an indictment of the Big Six: “The large national brewery companies charge higher prices for their beer than regional and small companies. Their prices have increased more rapidly than those charged by regional and small companies.

“These above average prices reflect, in large measure, the higher costs of selling, administration and distribution incurred by the large national brewery combines.”

The biggest price scandal concerned the new wave of British lagers. I point out in the book that such beers had little or nothing in common with the fine traditional beers of Germany and the then Czechoslovakia. I quoted a detailed report in the Guardian by Stuart Mansell who dismissed the brewers’ claims that the cost of lager reflected the longer brewing time needed: “Lager fermentation takes about three weeks compared to one week with most bitters. The valuable fermentation tanks and other capital equipment therefore turn out far less lager, and depreciation per pint must represent a significantly large sum – but however one does the figure work it’s hardly going to be more than 1p a pint more.”

And as Mansell pointed out, that 1p extra was easily recouped as the brewers paid less duty on lager than stronger bitters. I found the following:

Allied Breweries:

Skol OG 1037, 36½p per pint

Ind Coope Bitter, OG 1037, 30p per pint.

Bass Charrington

Tuborg OG 1030, 39p per pint

M&B Mild, 1034 OG, 28p per pint.

Courage

Kronenbourg 1041 OG, 36p per pint

Courage Best 1039 OG, 32p per pint.

Watney

Carlsberg Hof 1042 OG, 42p per pint

Trumans Tap Bitter 1039.5 OG, 37p per pint.

Whitbread

Heineken 1036 OG, 38p per pint

Wethered Trophy Bitter 1035.5 OG, 31p per pint.

(In the 1970s, beer was taxed on its original gravity, a measure of the “fermentable materials” used. Today duty is levied on alcohol by volume. Roughly speaking, beer with an OG of 1038 will have an ABV of 3.8 per cent, but this can vary.)

I pointed out that drinkers were not only paying through the nose for lager but were conned into thinking they were getting genuine continental beers.

“In spite of such names as Carlsberg, Norseman, Viking, Tuborg, Grunhalle (a Gothicised version of Greenhall), Brock, which supplements Hall & Woodhouse’s Badger beer and, most ludicrous of all, Hibrau from Guernsey, most British-brewed lagers are as European or Scandinavian as Chipping Sodbury on a wet Thursday.”

I ended the book with a call on the government to break up the Big Six and allow the breweries they had taken over to return to the families or groups that had previously owned them. The call fell on deaf ears but retribution came many years later. A report by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission in 1989 into the industry was so savage in its condemnation of the price-fixing and over-charging by the Big Six that the government was forced to act.

Its Beer Orders in the early 1990s led to most of the big brewers eventually quitting brewing. In their place came the modern breed of pub companies and an appalling record of charging high prices for beer. As the founder of Punch Taverns said: “I buy beer cheap and sell it dear: the difference is my profit.” In other words, stuff the consumer.

Of course, beer choice is demonstrably better today as a result of the rise of the craft beer movement. But let’s not kid ourselves. The global brewers and their pubco pals dominate the market and charge wickedly high prices for their products.

And in spite of the fancy names, the likes of Carlsberg, Stella Artois, Foster’s and Coors are all brewed in this country.

Which is where we came in. Plus ça change...